Doobie Doo

Veteran

my favorite artist/producer of all time finally gets some acknowledgement that he deserves. This is a big deal to me.

my favorite artist/producer of all time finally gets some acknowledgement that he deserves. This is a big deal to me.Curtis Mayfield Finally Gets a Definitive Biography. What Took So Long?

Curtis in 1972. (Photo by Michael Putland/Getty Images)

THE PITCH

- by Oliver Wang

Contributor

One of the most remarkable things about the new, definitive Curtis Mayfield biography, Traveling Soul, is that it took this long for someone to write one. In terms of influence and popularity, Mayfield’s stature in the 1960s through early ’70s easily puts him in the same conversation as such R&B icons as Marvin Gaye, Aretha Franklin, and James Brown. Yet somehow, his life has never been as lavishly chronicled. Written by Curtis’s son Todd, with help from music writer Travis Atria, Traveling Soul provides a long overdue corrective, not only in returning Curtis’s legacy into a proper light but also by offering revealing, intimate evaluation of him as a musical leader, business partner, friend, husband, and father. Traveling Soul serves as a vital reintroduction to one of soul music’s most important—yet under-considered—figures.

It’s staggering to contemplate just how prodigious Curtis was, beginning at age 8, when he taught himself the guitar and began to tour with the Chicago gospel outfit, the Northern Jubilee Singers. In his teens, he and a motley crew drawn from different doo-wop groups formed the Impressions, scoring a surprise Top 10 single in 1958 with “For Your Precious Love.” After then-lead singer Jerry Butler left to go solo, Curtis became the band’s de facto head. He was barely 16.

ADVERTISEMENT

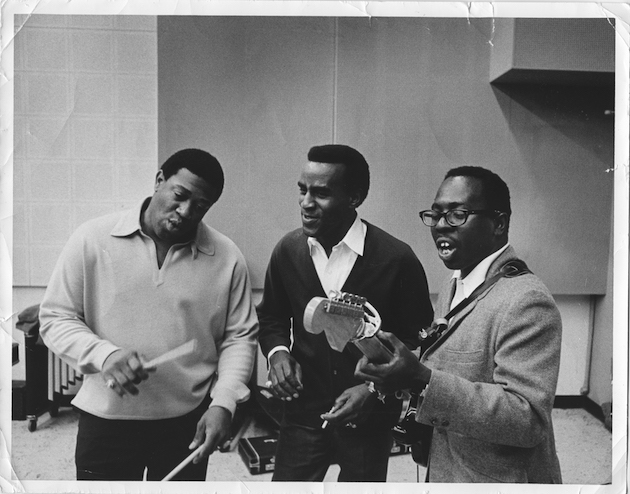

The Impressions briefly struggled to find its footing until Curtis penned their gold-selling “Gypsy Woman” in 1961. Chicago’s OKeh Records offered him a gig as a staff songwriter and Curtis quickly turned into one-man hit machine, writing and/or producing a parade of chart-toppers for the likes of Major Lance (“The Monkey Time”), Gene Chandler (“Nothing Can Stop Me”), Billy Butler (“I Can’t Work No Longer”), and others. Even though these songs didn’t feature his signature, fragile tenor, many of them sound indistinguishable from what Curtis was cooking up for he and the Impressions over at rival label, ABC-Paramount. Curtis was so talented, he could simply stockpile potential hits, randomly handing them off to whatever artist came asking for one. As Todd contends, “unlike at Motown, where a factory of writers created the hits, at OKeh, Curtis was the factory.”

Meanwhile, Curtis and the Impressions began to draw from “gospel’s deep, holy well,” perfecting a three-man vocal weave, with Curtis, Fred Cash, and Sam Gooden deftly trading off lead vocals and sliding into group harmonies. (To hear the effect at its most sublime, listen to “I’ve Been Trying” around the two-minute mark.) That style was common enough in gospel but it electrified pop listeners, propelling “It’s All Right” to become the Impressions’ best-selling single ever. But their next smash was even more iconic: “Keep On Pushing” became the first in a string of Civil Rights paeans, followed by “People Get Ready” and culminating in “We’re A Winner,” whose subtle message of racial pride was deemed too controversial for some white radio DJs to play. It went to No. 1 anyways.

Curtis was never the kind of songwriter to pen as on-the-nose an anthem as James Brown’s “(Say It Loud) I’m Black and I’m Proud,” and even his most politically charged albums never earned the same acclaim given Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On. Yet few other soul artists of that era seemed as socially engaged as Curtis. One of the great insights in Traveling Soul explains that Curtis’s decision to leave the Impressions in 1970 wasn’t just financial but also artistic. The group had an incredible run under his leadership, but with Curtis increasingly eager to speak to the tumult of the times, the group’s basic structure became a creative liability. “He couldn’t deliver lines in idiosyncratic ways,” writes Todd, “because he had two other guys whose job was to follow his lead. As a result, it changes the subject, the attitude, and the meaning he could imply behind his lyrics.” Being on his own was a way to be “funkier, freer” and sure enough, his debut solo album from 1970, Curtis,contains some of his most outspoken songs, including “Move On Up,” “The Other Side of Town,” and the solemn masterpiece of self-critique: “We People Who Are Darker Than Blue.”

By winter of 1971, Curtis agreed to record the soundtrack for an upcoming film about a drug dealer-turned-folk hero:Super Fly. It became, for better or for worse, Curtis’s most signature album. Todd suggests that creating it “allowed Dad to craft his most autobiographical lyrics ever” by drawing upon personal experiences in hardscrabble Chicago neighborhoods. As Curtis celebrated his 30th birthday in the summer of 1972, the Super Fly soundtrack became a runaway hit, the commercial capstone of his career. Yet even as the album marked a professional apogee, Traveling Soul reveals how Curtis’s personal life seemed to continually tumble towards new nadirs. Todd stresses how deeply insecure his father was throughout his life, a pathology rooted in an impoverished Chicago childhood in the 1940s and ’50s. Raised amidst both economic and emotional instability, Curtis became obsessed with the idea that “possessing a special talent earned control, and control brought security.” Curtis obviously cultivated a special talent, but his need for control undermined the security he craved. The book reminds us, ad nauseum, that Curtis was a Gemini; this is meant to explain his mercurial nature, where his loyalties could prove as unstable as his moods. “Only with music was he constant,” Todd writes.

For Super Fly, Curtis had called upon the Impressions’ longtime arranger, Johnny Pate, for help, but when Pate asked to share writing credits on two of the soundtrack’s songs, Curtis balked. The two men never worked together again. Likewise, Curtis also alienated manager Eddie Thomas, who had been at his side so long that Thomas had not only come up with the name “the Impressions,” but when Curtis created his own publishing company and label, he named it “Curtom,” i.e. Curtis + Thomas. As Todd grimly asserts, “when it came to money, power, and control, he wanted all of it,” even if that meant freezing out old friends and partners.

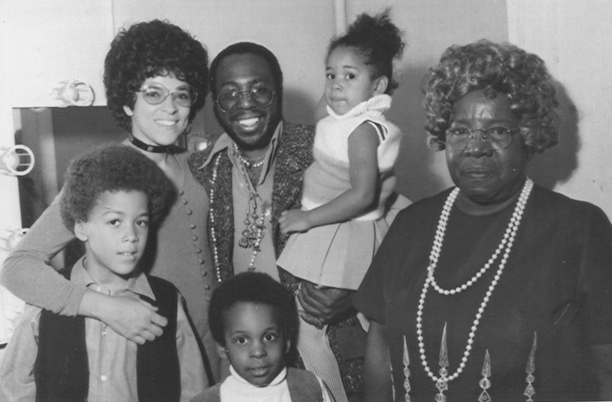

Meanwhile, Curtis’s home life was little better. ThoughTraveling Soul paints Curtis as a decent, semi-present father, the book chronicles the years of rampant infidelity and emotional neglect that Curtis’s various wives and lovers suffered through. By the mid-’70s, his children would witness signs of Curtis physically abusing his partners; while Todd is unsparing in detailing his father’s other foibles, describing Curtis’s abusive behavior as an “inexplicable occurrence of weakness” feels blatantly, frustratingly euphemistic.

Curtis certainly wouldn’t have been the first soul man whose virtuous public face masked a private life of discord. Gaye was the undisputed title-holder here, but his life, and especially his death (shot dead by his father at the age of 44), helped turn Gaye into a tragic figure of Aristotelianproportions. For all his own personal pathos, Curtis has never been mythologized in the same way. Instead, along with other R&B contemporaries of the 1960s, Curtis suffered through a slow decline into cultural irrelevance over the shifting course of pop music in the ’70s. Like many peers, he cut ill-advised disco albums, and even Traveling Soul writes off most of his ‘80s records as middling fare. The rise of hip-hop revived some interest in Curtis, but mostly via samples of his classic recordings rather than an embrace of his new ones. Then, in 1990, a freak, wind-whipped accident at a Brooklyn show brought a light fixture onto Curtis’s neck, rendering him a quadriplegic.

What most people remember of the aftermath is that Curtis still managed to record one more album—1996’s New World Order—even though his inoperative diaphragm required that he record his vocals while lying prone. The public rightfully lauded the album as a heroic comeback but whileNew World Order may have marked a bright spot, Todd writes of the bleak and despondent conditions that his father spent his last decade dwelling in, filled with physical agony and spiritual decay. For most of his life, Curtis’s guitar had been his “shield against the world” but his injury had permanently robbed him of that. In 1999, following a rapid decline in his health, Curtis died in Atlanta at the age of 59.

Traveling Soul only deepened my appreciation of Curtis’s musical genius, but I couldn’t help but be unsettled by its portrait of his fragility and insecurity. After finishing the book, I found myself repeatedly returning to the Impressions’ “I’m So Proud,” from 1964, one of their most delicate and enduring ballads. Previously, I dwelled on the glorious, multi-harmony hook–“I’m so proud of being loved by you”–but now, it’s the lyric after that haunts me. Curtis sings it solo: “And it would hurt / Hurt to know / If you ever were untrue.” With that one line, he pierces through the song’s aura of loving bliss and twists the hilt. The Curtis portrayed in Traveling Soul simply couldn’t help himself. His fear of losing control meant that even when penning an ode to love’s power, doubt lingered within, writing on for the darkness.

Curtis Mayfield Finally Gets a Definitive Biography. What Took So Long? | Pitchfork

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-699012-1341386519-7257.jpeg.jpg)

for peeping this breh. Y'all are dead on it, about him being underrated. Great all around musician; from his days of doo wop soul with the Impressions to his solo career. He also wrote a lot for other artists..... Aretha Franklin, Staples Singers, Gladys Knight and others. For brehs on here not down, check out his stuff and the soundtracks he did for himself and others. He is in the Stevie/ Prince mold. Not as known but very talented.

for peeping this breh. Y'all are dead on it, about him being underrated. Great all around musician; from his days of doo wop soul with the Impressions to his solo career. He also wrote a lot for other artists..... Aretha Franklin, Staples Singers, Gladys Knight and others. For brehs on here not down, check out his stuff and the soundtracks he did for himself and others. He is in the Stevie/ Prince mold. Not as known but very talented.