Crispr gene editing shown to permanently lower high cholesterol

Folks with hereditary high cholesterol would be able avoid lifelong medication.

Crispr gene editing shown to permanently lower high cholesterol

Folks with hereditary high cholesterol would be able avoid lifelong medication.

EMILY MULLIN, WIRED.COM - Wednesday at undefined

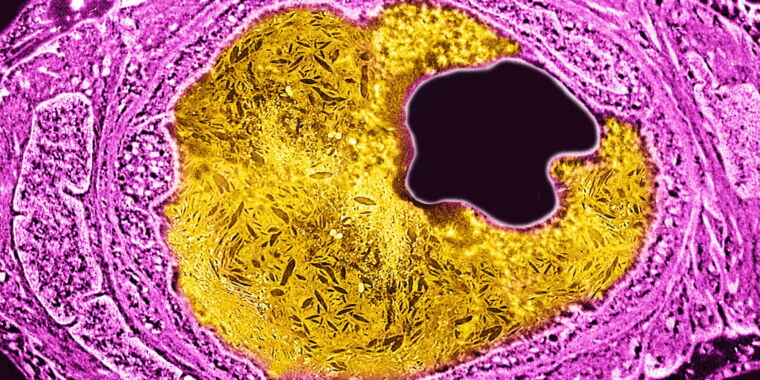

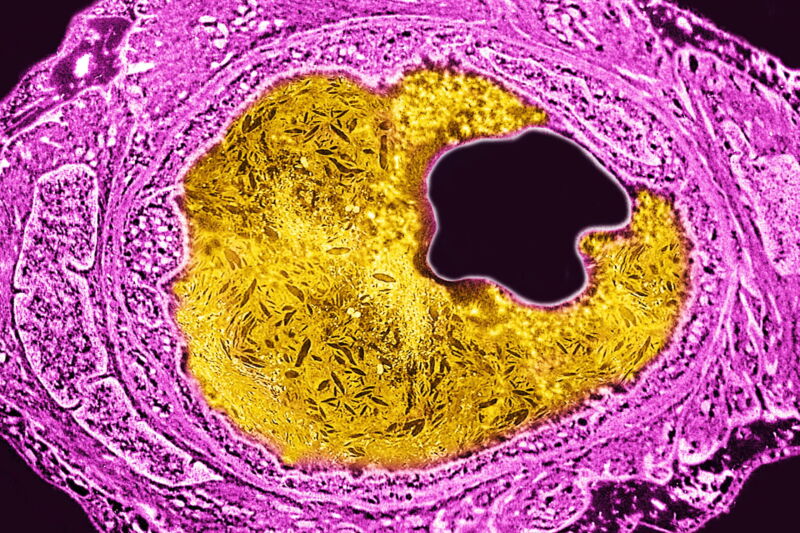

James Cavallini/Getty Images

109WITH

In a small initial test in people, researchers have shown that a single infusion of a novel gene-editing treatment can reduce cholesterol, the fatty substance that clogs and hardens arteries over time.

The experiment was carried out in 10 participants with an inherited condition that causes extremely high LDL, or “bad,” cholesterol levels, which can lead to heart attack at an early age. Despite being on cholesterol-lowering medications, the volunteers were already suffering from heart disease. They joined a trial in New Zealand and the United Kingdom run by Verve Therapeutics, a Cambridge, Massachusetts–based biotech company.

The first patient was treated just six months ago, and researchers are still following all of the participants. The preliminary results were presented at the American Heart Association’s annual meeting in Philadelphia on November 12.

Gene editing could provide a more lasting option for treating hereditary high cholesterol, which today requires long-term medication. “The current care consists of daily pills and intermittent injections that must be taken for decades. This places a very heavy treatment burden on patients, providers, and the health care system,” said Andrew Bellinger, chief scientific officer of Verve Therapeutics, at a news conference over the weekend.

But no one has ever used gene editing to lower cholesterol in people before. “This is a strategy that could be revolutionary,” said Karol Watson, a cardiologist at UCLA, during the news conference. “But we have to make sure it's safe.”

The treatment uses a newer, more precise form of Crispr called base editing to inactivate a gene in the liver called PCSK9. This gene plays a critical role in controlling LDL cholesterol in the blood. Instead of cutting genes, as Crispr is designed to do, base editing simply swaps one DNA letter for another. Verve’s treatment is designed to change an A to a G, which effectively turns the PCSK9gene off.

In a study published in the journal Circulation earlier this year, researchers from the company showed that the approach lowered bad cholesterol 49 to 69 percent in monkeys, depending on the dosage they received. Those reductions have now lasted two and a half years following a single dose of the therapy.

The current trial is for patients with familial hypercholesterolemia, a type of inherited high cholesterol that affects around 3 million people in the United States and Europe, combined. While the participants already had severe coronary artery disease, and some had previously experienced a heart attack, the company aims to eventually treat younger patients in order to prevent these outcomes. “We're envisioning that this will ultimately be a treatment that could be applied earlier in the disease course to younger patients who have very high lifetime risks,” Bellinger said.

Sanjay Rajagopalan, director of the Cardiovascular Research Institute at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, calls the results a “very exciting” proof of concept. But Rajagopalan, who wasn’t involved in the Verve study, says the main concern about any Crispr-based approach is the potential for off-target effects, in which unwanted cells or genes would unintentionally be edited.

“This is a gene editing study. You’re changing the genome forever,” said Watson, echoing the same point. “Safety is going to be of the utmost importance.”

During the press conference, Bellinger said the company has not detected any off-target editing in human liver cells treated with its experimental therapy. He said unwanted genetic edits could potentially cause health problems such as cancer, although he believes the risk is very low. “Ultimately, we will have to run those larger studies with observation for those outcomes,” he said.

Verve Therapeutics plans to enroll more patients in the trial next year, including in the US. In November 2022 the US Food and Drug Administration put a pause on the trial’s start, asking for more information on the possibility of off-target edits in other cells and whether the gene edit could be passed down to children whose parents get the therapy. But the agency lifted the hold in October, allowing the company to begin enrolling patients in the US.

And like any novel therapy, Rajagopalan points out, “the treatment would have to compete with other safe treatment approaches that are already available.” For instance, statins and other lipid-lowering drugs are known to be safe and effective. “However,” he continues, “the convenience of one treatment that can fix the disorder permanently is extremely attractive.”

This story originally appeared on wired.com.