A radical and growing organization of ‘constitutional sheriffs’ is promoting defiance of federal laws it doesn’t like.

In the minutes before he was killed as he apparently tried to draw a 9mm pistol on law enforcement officials attempting to arrest him at an Oregon roadblock early this year, antigovernment militant Robert “LaVoy” Finicum repeatedly shouted out to officers that he was on his way to meet with “the sheriff.”

Occupation spokesman LaVoy Finicum was shot to death in Oregon by law enforcement officers after apparently trying to draw a gun as they tried to arrest him. (AP Images/Rick Bowmer)

And, indeed, Grant County Sheriff Glenn Palmer was in John Day, Ore., waiting for a town hall meeting 90 minutes later featuring principals of the then 24-day-old occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, including Finicum and occupation leader Ammon Bundy. Both Palmer and Bundy were expected to speak at the gathering that had been organized by occupation sympathizers.

But Palmer, whose county adjoins Harney County, where the occupation took place, had been told nothing of the Jan. 26 roadblock — for very good reasons.

He had already met twice with leaders of the occupation, and witnesses described how he had them autograph his pocket copy of the Constitution. He had referred to the occupiers as “patriots” and endorsed their demands for the release of two ranchers imprisoned for arson on public lands and the departure of the FBI. He boasted about his refusal to enforce laws that he believed were unconstitutional, and he was known for picking fights with land use officials. Unlike the sheriffs of the four other adjoining counties, he had sent no deputies to help out in Harney County. Glenn Palmer was not trusted in law enforcement circles.

So when organizing began for the arrests of the people who had broken into, occupied, and trashed the Malheur park building, officials moved their plans for a roadblock from Grant to Harney County. Then, apparently fearing Palmer might warn off the militants, the officials decided not to tell him anything about it.

In the aftermath of the shutdown of the Malheur occupation — a total of 25 people were charged in connection with the occupation in the weeks after Finicum’s death — Palmer described the roadblock as an “ambush,” sounding remarkably similar to militants who claimed Finicum’s shooting was an assassination. That drew an immediate rebuke from the Oregon State Sheriffs’ Association, which told The Oregonian that it was actually a carefully planned operation “to take into custody armed persons who had openly engaged in a variety of criminal activities.”

In the following days, nine complaints — two of them from John Day officials, including the town’s police chief — were lodged against Palmer, who did not return repeated requests for comment from the Intelligence Report, with the Department of Public Safety Standards and Training. And the state Department of Justice has now opened a criminal investigation into one of those complaints.

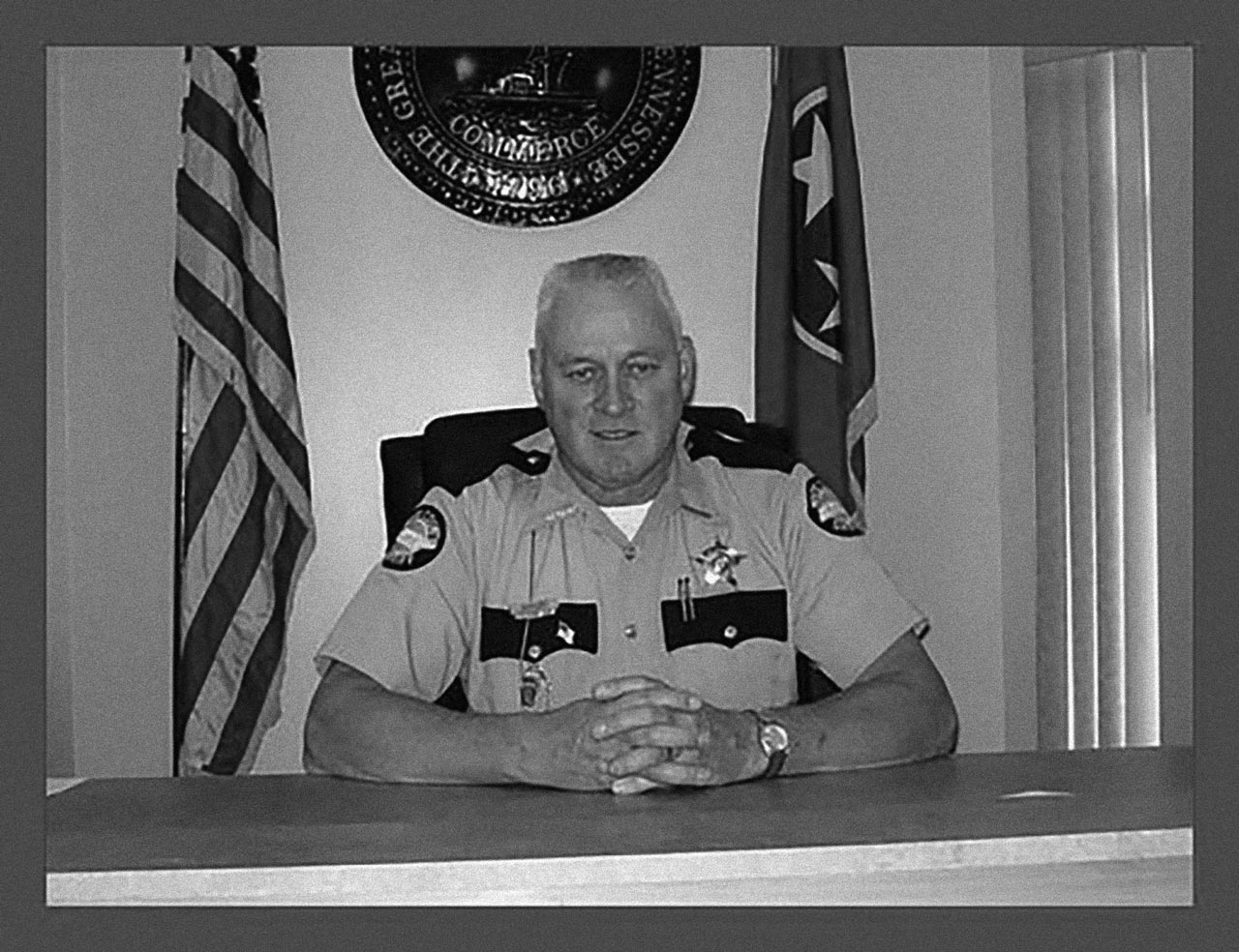

Glenn Palmer (also pictured in the top header), the sheriff of a nearby county, described the roadblock as an “ambush” and made it clear that he sympathized with occupation leader Ammon Bundy and his father, Cliven Bundy. (Facebook)

Sheriff Palmer, who is running for his fifth four-year term this November, is a dramatic example of a new kind of radical that is springing up around the country — the so-called “constitutional sheriff.” In fact, in 2012 Palmer became the very first to be named “Sheriff of the Year” by the Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association (CSPOA), a far-right group that calls itself “the last line of defense standing between the overreaching government and your Constitutionally guaranteed rights.” The CSPOA has long claimed the support of more than 400 sheriffs.

The group says it is part of “a growing movement of public officials who are drawing a line in the sand” by “interposing themselves between the sometimes overreaching Federal Government and your constitutionally guaranteed rights.” It claims that local county sheriffs can stop outside law enforcement officials from enforcing laws they deem unconstitutional. “The sheriff,’ it says, “is the highest elected official in the county and has the authority to stop this insanity.”

Ammon Bundy (AP Images/Rick Bowmer)

At a time when anger at the federal government over issues like land use and environmental regulation in the rural West is running higher than it has in years, the CSPOA and a closely related group, the Oath Keepers, are working tirelessly to make inroads into the ranks of American law enforcement. Sheriffs around the country report that they regularly hear from the groups, by phone, fax and other means, as they attempt to enlarge support for their positions. The country has rarely, if ever, seen such a concerted and long-term effort to bring sheriffs and other law enforcement officials to an ideology that proposes to openly defy federal law.

Cliven Bundy (AP Images/John Locher)

The rise of the CSPOA comes in the context of an antigovernment “Patriot” movement that has grown enormously since the election of Barack Obama in 2008, from about 150 groups that year to almost 1,000 today. CSPOA members have joined in the battle over the use of public lands — such as that at Malheur and, in 2014, a similar but larger armed standoff at the Nevada ranch owned by Ammon Bundy’s father, Cliven — and even more so the fight against further gun control. In 2013, many members wrote Vice President Joe Biden to say, as Palmer wrote, that they would not “permit” any “federal incursion” into their counties “where any type of gun control legislation aimed at disarming law abiding citizens is the goal.”

How strong are the CSPOA and its leader, former Arizona sheriff Richard Mack? Does Mack, who once worked for the radical gun rights group Gun Owners of America, really have the support of hundreds of the nation’s 3,000-plus sheriffs in defying the rule of law? The Intelligence Report recently tried to find out.

The radical ideas of Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association leader Richard Mack have gotten a sympathetic hearing from sheriffs including Cameron Noel, Ronald Bruce and Oddie Shoupe. (AP Images/Marc Levy)

The Radicals

Richard Mack, who formed the CSPOA in 2011 with a promise to persuade local governments to issue declarations to the federal government “regarding the abuses we will no longer tolerate,” has repeatedly declined to publish or provide a list of the sheriffs he says are backers or members of the CSPOA. Although media outlets have reported that he claims more than 400 supporters or members, Mack told the Reportthat the CSPOA had only “trained” that number of sheriffs.

He said the focus of his group was not on recruiting members but on persuading sheriffs to adopt the group’s positions. But he also claimed the CSPOA has “about 5,000 members,” including sheriffs, police chiefs, peace officers and other citizens. He said he didn’t know how many of those were sheriffs, but noted that the CSPOA is now making a major effort to run sheriff’s candidates.

In 2014, however, the CSPOA did publish a list (since taken down) of 485 sheriffs who, in the group’s words, “have vowed to uphold and defend the Constitution against Obama’s unconstitutional gun measures.” Although that is not the same thing as being CSPOA supporters or members, the number of 485 is notably similar to the number of CSPOA trainees claimed by Mack.

The Report worked in May and June to contact all the sheriffs listed to get a sense of their support for the CSPOA and its policies. A small percentage of those men and women had retired, died or lost bids for reelection. A much larger percentage failed to respond to phone calls or emailed questionnaires.

In the minutes before he was killed as he apparently tried to draw a 9mm pistol on law enforcement officials attempting to arrest him at an Oregon roadblock early this year, antigovernment militant Robert “LaVoy” Finicum repeatedly shouted out to officers that he was on his way to meet with “the sheriff.”

Occupation spokesman LaVoy Finicum was shot to death in Oregon by law enforcement officers after apparently trying to draw a gun as they tried to arrest him. (AP Images/Rick Bowmer)

And, indeed, Grant County Sheriff Glenn Palmer was in John Day, Ore., waiting for a town hall meeting 90 minutes later featuring principals of the then 24-day-old occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, including Finicum and occupation leader Ammon Bundy. Both Palmer and Bundy were expected to speak at the gathering that had been organized by occupation sympathizers.

But Palmer, whose county adjoins Harney County, where the occupation took place, had been told nothing of the Jan. 26 roadblock — for very good reasons.

He had already met twice with leaders of the occupation, and witnesses described how he had them autograph his pocket copy of the Constitution. He had referred to the occupiers as “patriots” and endorsed their demands for the release of two ranchers imprisoned for arson on public lands and the departure of the FBI. He boasted about his refusal to enforce laws that he believed were unconstitutional, and he was known for picking fights with land use officials. Unlike the sheriffs of the four other adjoining counties, he had sent no deputies to help out in Harney County. Glenn Palmer was not trusted in law enforcement circles.

So when organizing began for the arrests of the people who had broken into, occupied, and trashed the Malheur park building, officials moved their plans for a roadblock from Grant to Harney County. Then, apparently fearing Palmer might warn off the militants, the officials decided not to tell him anything about it.

In the aftermath of the shutdown of the Malheur occupation — a total of 25 people were charged in connection with the occupation in the weeks after Finicum’s death — Palmer described the roadblock as an “ambush,” sounding remarkably similar to militants who claimed Finicum’s shooting was an assassination. That drew an immediate rebuke from the Oregon State Sheriffs’ Association, which told The Oregonian that it was actually a carefully planned operation “to take into custody armed persons who had openly engaged in a variety of criminal activities.”

In the following days, nine complaints — two of them from John Day officials, including the town’s police chief — were lodged against Palmer, who did not return repeated requests for comment from the Intelligence Report, with the Department of Public Safety Standards and Training. And the state Department of Justice has now opened a criminal investigation into one of those complaints.

Glenn Palmer (also pictured in the top header), the sheriff of a nearby county, described the roadblock as an “ambush” and made it clear that he sympathized with occupation leader Ammon Bundy and his father, Cliven Bundy. (Facebook)

Sheriff Palmer, who is running for his fifth four-year term this November, is a dramatic example of a new kind of radical that is springing up around the country — the so-called “constitutional sheriff.” In fact, in 2012 Palmer became the very first to be named “Sheriff of the Year” by the Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association (CSPOA), a far-right group that calls itself “the last line of defense standing between the overreaching government and your Constitutionally guaranteed rights.” The CSPOA has long claimed the support of more than 400 sheriffs.

The group says it is part of “a growing movement of public officials who are drawing a line in the sand” by “interposing themselves between the sometimes overreaching Federal Government and your constitutionally guaranteed rights.” It claims that local county sheriffs can stop outside law enforcement officials from enforcing laws they deem unconstitutional. “The sheriff,’ it says, “is the highest elected official in the county and has the authority to stop this insanity.”

Ammon Bundy (AP Images/Rick Bowmer)

At a time when anger at the federal government over issues like land use and environmental regulation in the rural West is running higher than it has in years, the CSPOA and a closely related group, the Oath Keepers, are working tirelessly to make inroads into the ranks of American law enforcement. Sheriffs around the country report that they regularly hear from the groups, by phone, fax and other means, as they attempt to enlarge support for their positions. The country has rarely, if ever, seen such a concerted and long-term effort to bring sheriffs and other law enforcement officials to an ideology that proposes to openly defy federal law.

Cliven Bundy (AP Images/John Locher)

The rise of the CSPOA comes in the context of an antigovernment “Patriot” movement that has grown enormously since the election of Barack Obama in 2008, from about 150 groups that year to almost 1,000 today. CSPOA members have joined in the battle over the use of public lands — such as that at Malheur and, in 2014, a similar but larger armed standoff at the Nevada ranch owned by Ammon Bundy’s father, Cliven — and even more so the fight against further gun control. In 2013, many members wrote Vice President Joe Biden to say, as Palmer wrote, that they would not “permit” any “federal incursion” into their counties “where any type of gun control legislation aimed at disarming law abiding citizens is the goal.”

How strong are the CSPOA and its leader, former Arizona sheriff Richard Mack? Does Mack, who once worked for the radical gun rights group Gun Owners of America, really have the support of hundreds of the nation’s 3,000-plus sheriffs in defying the rule of law? The Intelligence Report recently tried to find out.

The radical ideas of Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association leader Richard Mack have gotten a sympathetic hearing from sheriffs including Cameron Noel, Ronald Bruce and Oddie Shoupe. (AP Images/Marc Levy)

The Radicals

Richard Mack, who formed the CSPOA in 2011 with a promise to persuade local governments to issue declarations to the federal government “regarding the abuses we will no longer tolerate,” has repeatedly declined to publish or provide a list of the sheriffs he says are backers or members of the CSPOA. Although media outlets have reported that he claims more than 400 supporters or members, Mack told the Reportthat the CSPOA had only “trained” that number of sheriffs.

He said the focus of his group was not on recruiting members but on persuading sheriffs to adopt the group’s positions. But he also claimed the CSPOA has “about 5,000 members,” including sheriffs, police chiefs, peace officers and other citizens. He said he didn’t know how many of those were sheriffs, but noted that the CSPOA is now making a major effort to run sheriff’s candidates.

In 2014, however, the CSPOA did publish a list (since taken down) of 485 sheriffs who, in the group’s words, “have vowed to uphold and defend the Constitution against Obama’s unconstitutional gun measures.” Although that is not the same thing as being CSPOA supporters or members, the number of 485 is notably similar to the number of CSPOA trainees claimed by Mack.

The Report worked in May and June to contact all the sheriffs listed to get a sense of their support for the CSPOA and its policies. A small percentage of those men and women had retired, died or lost bids for reelection. A much larger percentage failed to respond to phone calls or emailed questionnaires.