Ya' Cousin Cleon

OG COUCH CORNER HUSTLA

Companies Steal $15 Billion From Their Employees Every Year

The amount of money employers take from their employees each year–by refusing to pay overtime or misclassifying workers so they don’t get minimum wage–is larger than the value of all the theft by criminals.

When employers fail to pay overtime, withhold tips from waitresses and waiters, or misclassify workers as exempt from minimum wage regulations, they’re stealing income from the poorest members of society. “Wage theft,” the collective term for this practice, can take many forms. But it comes down to something simple: bosses stiffing workers out what they are legally owed.

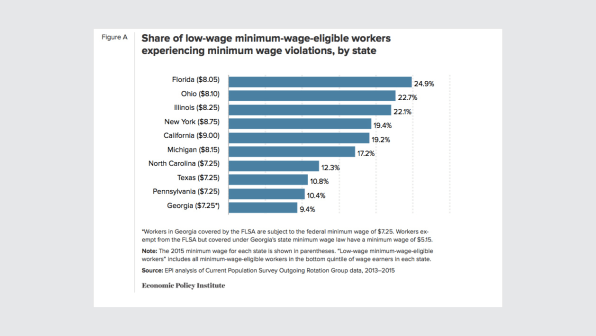

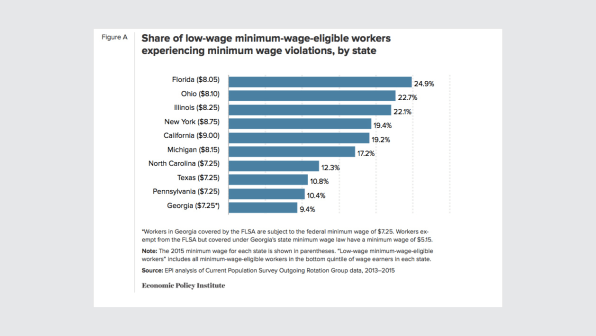

This workplace larceny is worse than you might think. The Economic Policy Institute, a think-tank that investigates labor issues, analyzed records for the 10 most populous states. Looking just at one form of wage theft–failure to pay minimum wages in each state–it documents $8 billion in annual underpayments. Extrapolated across the U.S. as a whole, it calculates a total of $15 billion a year in employer misappropriation, which is more than the value of all the property stolen during robberies, burglaries, and auto thefts across the country.

Workers suffering minimum wage violations lose an average of $64 per week, almost a quarter of their weekly earnings.

The report finds 2.4 million workers affected across the ten states: California, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Michigan, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Texas. And it says workers suffering minimum wage violations lose an average of $64 per week, almost a quarter of their weekly earnings. An average wage theft victim earns just $10,500 in wages a year–and loses up to $3,300 of that to unscrupulous bosses.

“Property crime is a better understood, more tangible form of crime than wage theft, and federal, state, and local governments spend tremendous resources to combat it,” the report, written by EPI analyst David Cooper and research assistant Teresa Kroeger, says. “In contrast, lawmakers in much of the country allocate little, if any, resources to fighting wage theft, yet the cost of wage theft is at least comparable to–and likely much higher than–the cost of property crime.”

Cooper and Kroeger say that wage theft could be reduced through better enforcement of labor laws, including increasing penalties for violators, protecting workers from retaliation, and improving collective bargaining rights. It notes that the U.S. Department of Labor, which is responsible for investigating minimum violations, is chronically under-staffed. In 2015, its Wage and Hour Division (WHD) employed about the same number of investigators as 70 years ago–about 1000–despite a huge expansion of the economy over that time. The U.S. workforce is about six times larger today (135 million in 2015) compared to the 1940s (22.6 million in 1948).

The Obama Administration expanded the WHD from 700 to 1,000 staff and appointed the first WHD administrator in more than a decade (other appointees had been held up in Senate confirmation battles). David Weil, a professor at Boston University and author of the book The Fissured Workplace: Why Work Became So Bad for So Many and What Can Be Done To Improve It, is credited with stepping up misclassification investigations and helping to prosecute several offenders of labor law. By contrast, President Trump has yet to appoint a WHD administrator (or many other positions at the U.S. Department of Labor). His original choice for Secretary of Labor, Andrew Puzder–a rapid opponent of minimum wage laws–was never confirmed amid domestic abuse allegations. Labor Secretary Alex Acosta, Trump’s second choice, is considered to be more favorable towards labor. But it remains to be seen how independent he’ll be from the White House and whether he builds on the enforcement regime of the last administration.

Though it might be nice to think that employers wouldn’t need reminding of their responsibilities, or that workers (or their unions, if they have one–which they probably don’t) could enforce the rules, the EPI doesn’t sound hopeful. Enforcement makes the difference over time, it says (a point that Weil and other labor advocates echo). “The ability of employers to steal earned wages from their employees–largely with impunity–is but one more factor that has kept a generation of American workers from achieving greater improvements in their standard of living,” it says. “Lawmakers who care about the long-term economic health of American households and the ability of ordinary working people to get ahead should be paying more attention to whether those workers are actually being paid all the wages they have earned.”

The amount of money employers take from their employees each year–by refusing to pay overtime or misclassifying workers so they don’t get minimum wage–is larger than the value of all the theft by criminals.

When employers fail to pay overtime, withhold tips from waitresses and waiters, or misclassify workers as exempt from minimum wage regulations, they’re stealing income from the poorest members of society. “Wage theft,” the collective term for this practice, can take many forms. But it comes down to something simple: bosses stiffing workers out what they are legally owed.

This workplace larceny is worse than you might think. The Economic Policy Institute, a think-tank that investigates labor issues, analyzed records for the 10 most populous states. Looking just at one form of wage theft–failure to pay minimum wages in each state–it documents $8 billion in annual underpayments. Extrapolated across the U.S. as a whole, it calculates a total of $15 billion a year in employer misappropriation, which is more than the value of all the property stolen during robberies, burglaries, and auto thefts across the country.

Workers suffering minimum wage violations lose an average of $64 per week, almost a quarter of their weekly earnings.

The report finds 2.4 million workers affected across the ten states: California, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Michigan, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Texas. And it says workers suffering minimum wage violations lose an average of $64 per week, almost a quarter of their weekly earnings. An average wage theft victim earns just $10,500 in wages a year–and loses up to $3,300 of that to unscrupulous bosses.

“Property crime is a better understood, more tangible form of crime than wage theft, and federal, state, and local governments spend tremendous resources to combat it,” the report, written by EPI analyst David Cooper and research assistant Teresa Kroeger, says. “In contrast, lawmakers in much of the country allocate little, if any, resources to fighting wage theft, yet the cost of wage theft is at least comparable to–and likely much higher than–the cost of property crime.”

Cooper and Kroeger say that wage theft could be reduced through better enforcement of labor laws, including increasing penalties for violators, protecting workers from retaliation, and improving collective bargaining rights. It notes that the U.S. Department of Labor, which is responsible for investigating minimum violations, is chronically under-staffed. In 2015, its Wage and Hour Division (WHD) employed about the same number of investigators as 70 years ago–about 1000–despite a huge expansion of the economy over that time. The U.S. workforce is about six times larger today (135 million in 2015) compared to the 1940s (22.6 million in 1948).

The Obama Administration expanded the WHD from 700 to 1,000 staff and appointed the first WHD administrator in more than a decade (other appointees had been held up in Senate confirmation battles). David Weil, a professor at Boston University and author of the book The Fissured Workplace: Why Work Became So Bad for So Many and What Can Be Done To Improve It, is credited with stepping up misclassification investigations and helping to prosecute several offenders of labor law. By contrast, President Trump has yet to appoint a WHD administrator (or many other positions at the U.S. Department of Labor). His original choice for Secretary of Labor, Andrew Puzder–a rapid opponent of minimum wage laws–was never confirmed amid domestic abuse allegations. Labor Secretary Alex Acosta, Trump’s second choice, is considered to be more favorable towards labor. But it remains to be seen how independent he’ll be from the White House and whether he builds on the enforcement regime of the last administration.

Though it might be nice to think that employers wouldn’t need reminding of their responsibilities, or that workers (or their unions, if they have one–which they probably don’t) could enforce the rules, the EPI doesn’t sound hopeful. Enforcement makes the difference over time, it says (a point that Weil and other labor advocates echo). “The ability of employers to steal earned wages from their employees–largely with impunity–is but one more factor that has kept a generation of American workers from achieving greater improvements in their standard of living,” it says. “Lawmakers who care about the long-term economic health of American households and the ability of ordinary working people to get ahead should be paying more attention to whether those workers are actually being paid all the wages they have earned.”