You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

"Cause the greatest rapper of all time died on March 9th"

- Thread starter I love Latina women

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?He bodied this verse

The one and only Christopher "The Notorious B.I.G." Wallace! RIP BIG!

The one and only Christopher "The Notorious B.I.G." Wallace! RIP BIG!

If Nas never existed I would consider Biggie the GOAT. He was just the most well balanced, naturally gifted MC ever. I still think about how his career would've went if he lived constantly. Rest in peace to Chris Wallace. The one and only King Of New York.

Last edited:

I love Latina women

Veteran

beenz

Rap Guerilla

I remember waking up that Sunday morning when I heard the news via MTV. I was in disbelief and sad as hell. Dude was my favorite rapper at the time. Hell, he was a lot of people's favorite rapper back then.

I love Latina women

Veteran

As I listen to Biggie and think back on when he was still here, I think about how much things have changed since his death.

Hip Hop and Rap music is like The Twilight Zone these days.

It's crazy when u think about how different things were back then.

Hip Hop and Rap music is like The Twilight Zone these days.

It's crazy when u think about how different things were back then.

Rapmastermind

Superstar

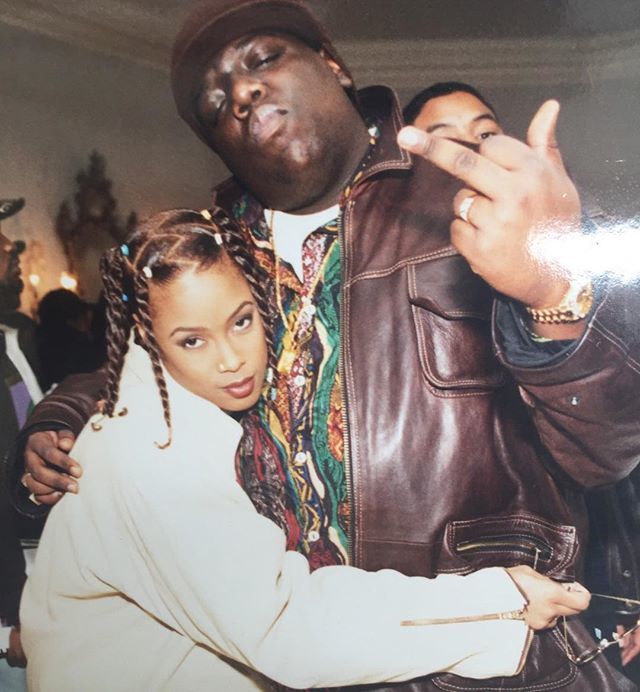

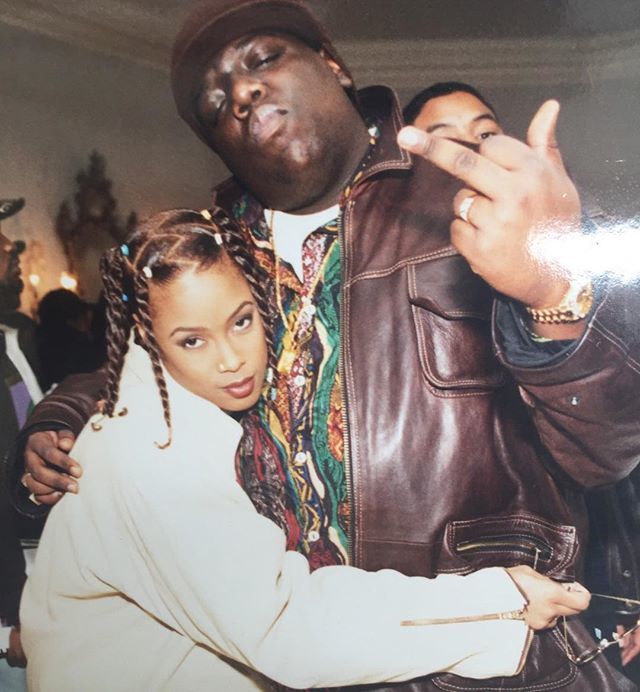

Da Brat posted this photo, I think her and Biggie's "Da B Side" was always slept on. I loved it in the "Bad Boys movie and soundtrack:

"nikka, close your eyes, 'cause you already see

The Notorious B, R, A, T" - Da Brat

"The raw combination, the destination

Number one tote a gun with no hesitation

Live with the funkdafied cutie pie

Gat by the thigh, the Smalls by her side

If you fukk with her you got to fukk with me

And we'll be rapping at your motherfukkin' eulogy, so" - B.I.G.

Long Live The King.............

"nikka, close your eyes, 'cause you already see

The Notorious B, R, A, T" - Da Brat

"The raw combination, the destination

Number one tote a gun with no hesitation

Live with the funkdafied cutie pie

Gat by the thigh, the Smalls by her side

If you fukk with her you got to fukk with me

And we'll be rapping at your motherfukkin' eulogy, so" - B.I.G.

Long Live The King.............

RIP

shawntitan

All Star

Still hoping a better copy of this will pop up someday...

I’ll Always Love Big Poppa: How Biggie Smalls Helped Me To Understand My Parents’ Deaths

Brittany Braithwaite

33 minutes ago

Filed to: NOTORIOUS B.I.G.

442

1

Rapper Notorious B.I.G., aka Biggie Smalls, aka Chris Wallace rolls a cigar outside his mother’s house in Brooklyn.

Photo: Clarence Davis (NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images)

On March 9, 1997, rapper Biggie Smalls, born Christopher Wallace, had his life taken way too early. He was 24 years old. He was gunned down after leaving an industry party in Los Angeles, six months after the death of rapper Tupac Shakur. Being from Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, and seeing how this entire community came together to mourn — by pouring into the streets and openly grieving — helped me learn how to understand death and loss in a way that I didn’t get at home.

I was one month shy of my second birthday when my biological mother died. I don’t remember anything about my mother’s death, her funeral, or what happened immediately after. I have no memory of my mother. I don’t know what she smelt like. I cannot recall what her voice sounded like, how she laughed, or how she walked. All I had was a photo album of pictures of her with her friends, ex-lovers, and middle school class. Two years later, my father would lose his battle to Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. I remembered some things about my father. How tall he was, and how white his teeth seemed to be. I have memories of a trip to the zoo, him purchasing me a life size Barney, and giving me a puppy who we named Matrix. While I didn’t remember much about either of them, one thing was true —- they both were gone before my first day of kindergarten.

Although I was far too young to process my parent’s deaths when I was 7, I was clear that Biggie Smalls had died, that he wasn’t coming back, and that many people that I knew and loved were really upset, a phenomenon I would later learn was called grief.

storybreak-theroot-afropicker");">

I remember returning to school the week after Biggie’s death. I attended a small Christian school in Bed Stuy—I jokingly say I attended a “historically black elementary school.” Murder, violence, drugs, territory, beef—none of that was fictitious to us. Many of us knew and loved someone who had been a victim of gun violence. We tried to keep our whispering down; we weren’t even supposed to talk about rap music—it was the “devil’s music,” according to the school administrators. Even though we were in first grade, my classmates and I knew all the words to “Big Poppa,” “Juicy,” and “One More Chance.” While our understanding of the world was still being crafted, we connected with the realities in BIG’s songs —because for Black kids growing up in Bed Stuy, those were some of our realities too.

BIG’s life meant a lot to us, but his death meant more to me.

I always knew I wasn’t like the other children. I would listen to adults in my family stumble over questions from school administrators about about my parents. Where were they? How did they die? What was I feeling? They would hush a rowdy uncle when he would start reminiscing about good times with Strike (my father) or quickly change the conversation when the topic of how fashionable Delores (my mother) came up.

I can only hope that they were trying to shield me from hurt, but when it came to discussing my parents death, I always felt alone. I had so many questions about death and dying. Where did they go when they died? How did they split their time between the cemetery and heaven? If they were in heaven why do we keep bringing flowers to this cemetery in New Jersey? My family made frequent visits to my parents’ graves (holidays, birthdays, anniversaries of their death, all the days). That’s how they grieved. I preferred to grieve differently but at 5 I had no platform to voice my concerns. I had no one to talk to.

I spent too much time feeling angry that I didn’t have my own memories of my parents. And the memories that other people had, they seemed to hold onto tightly, rarely sharing them with me. Because I didn’t know everything about them, I felt like I couldn’t love them like everyone else. BIG’s death showed me how diverse groups of people who had birthed him, recorded music with him, mentored him, and some (like me) who had just listened to his music. We all had different relationships with him — but all loved him. I could create my own memories of my parents and love them for that, always.

storybreak-theroot-afropicker");">

I remember the day when people came back to the block after standing on Fulton Street watching the procession of BIG’s hearse through the streets. I was home because I was 7, but I remember people saying “I can’t believe he’s gone.” I felt the sadness and heaviness of my community’s loss in particular; as if I had lost someone. The air was heavy, and people were mad at the West Coast, where I had never been.

The funeral procession of rapper Biggie Smalls passes as mourners line the streets near the building where the slain rapper once lived on St. James Place in the Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn on March 18, 1997.

Photo: AP Photo/Mark Lennihan

I remember watching the news footage of people in the street when they started playing “Hypnotize” to the crowd. I knew that it was okay to celebrate life and what people had given you while they were on earth. I wanted to know what my parents left behind —- where could I find the joy in their existence like people found in Biggie’s songs when Mrs. Wallace returned home to Bed Stuy.

I was never told that crying, or feeling angry, and upset was okay. That these were normal and just reactions to death. People pouring into the streets, crying publicly at award shows and TV interviews showed me that I didn’t need to cry in the closet or the bathroom. That there was nothing to be ashamed of. My pain was valid and all people feel that as a part of life. I was not alone. BIG’s death normalized grief for me.

More than that day, I remember the songs and videos that came out following his death. “I’ll Be Missing You” and “We’ll Always Love Big Poppa” especially because they have children in them. Every time these videos came on, I would stand directly in front of the TV mesmerized, and singing along with Diddy (then Puff Daddy), Faith Evans, and 112. I remember Diddy rapping, “In the future, I can’t wait to see if you’ll open up the gates for me,” and children dressed in all white running into what looked like forever, one of them his daughter Tyanna. Years after Biggie’s death I would think about his children. They were rich but would they be like me, orphans? Biggie’s children, Tyanna was 3 years old and Christopher Wallace Jr. was only 4 months old at the time of their father’s death. Would they remember their father? Have someone to talk to about his death? Did they secretly cry in the bathroom or the closet when they missed him? Learn the word grief before they were in high school?

Less than a month after Biggie’s death, “Life After Death” was released. To me, this was BIG living beyond the grave. It allowed me to move past the memories of my father’s funeral, what those tiny red roses that we placed on his coffin smelled like. My father, my mother, and even BIG had more living to do after the funeral services were over. Every time I heard a song from “Life After Death” I believed that more and more. My parents did not leave me an album to be released posthumously, but they created me. I am my parent’s legacy — I get to be that. I am a living manifestation of their hopes, dreams, and the continuance of their lives here on the earth. I don’t just believe that they are just resting, but rather that they are here resisting, creating joy, and building black futures alongside me and inside me every day.

I loved Notorious BIG, who made music about surviving and thriving despite the odds. That’s what I had to do as a Black girl who lost both of her parents while growing up in Bed Stuy in the 1990s. This would change a little bit after a few women’s studies courses and a deep dive into Joan Morgan’s When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost: My Life as a Hip Hop Feminist, nevertheless, Biggie still has a place on my altar and in my heart today because his death and how the world reacted to it helped me do what I know now is, grieve.

https://www.theroot.com/i-ll-always-love-big-poppa-how-biggie-smalls-helped-me-1823628081

Brittany Braithwaite

33 minutes ago

Filed to: NOTORIOUS B.I.G.

442

1

Rapper Notorious B.I.G., aka Biggie Smalls, aka Chris Wallace rolls a cigar outside his mother’s house in Brooklyn.

Photo: Clarence Davis (NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images)

On March 9, 1997, rapper Biggie Smalls, born Christopher Wallace, had his life taken way too early. He was 24 years old. He was gunned down after leaving an industry party in Los Angeles, six months after the death of rapper Tupac Shakur. Being from Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, and seeing how this entire community came together to mourn — by pouring into the streets and openly grieving — helped me learn how to understand death and loss in a way that I didn’t get at home.

I was one month shy of my second birthday when my biological mother died. I don’t remember anything about my mother’s death, her funeral, or what happened immediately after. I have no memory of my mother. I don’t know what she smelt like. I cannot recall what her voice sounded like, how she laughed, or how she walked. All I had was a photo album of pictures of her with her friends, ex-lovers, and middle school class. Two years later, my father would lose his battle to Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. I remembered some things about my father. How tall he was, and how white his teeth seemed to be. I have memories of a trip to the zoo, him purchasing me a life size Barney, and giving me a puppy who we named Matrix. While I didn’t remember much about either of them, one thing was true —- they both were gone before my first day of kindergarten.

Although I was far too young to process my parent’s deaths when I was 7, I was clear that Biggie Smalls had died, that he wasn’t coming back, and that many people that I knew and loved were really upset, a phenomenon I would later learn was called grief.

storybreak-theroot-afropicker");">

I remember returning to school the week after Biggie’s death. I attended a small Christian school in Bed Stuy—I jokingly say I attended a “historically black elementary school.” Murder, violence, drugs, territory, beef—none of that was fictitious to us. Many of us knew and loved someone who had been a victim of gun violence. We tried to keep our whispering down; we weren’t even supposed to talk about rap music—it was the “devil’s music,” according to the school administrators. Even though we were in first grade, my classmates and I knew all the words to “Big Poppa,” “Juicy,” and “One More Chance.” While our understanding of the world was still being crafted, we connected with the realities in BIG’s songs —because for Black kids growing up in Bed Stuy, those were some of our realities too.

BIG’s life meant a lot to us, but his death meant more to me.

I always knew I wasn’t like the other children. I would listen to adults in my family stumble over questions from school administrators about about my parents. Where were they? How did they die? What was I feeling? They would hush a rowdy uncle when he would start reminiscing about good times with Strike (my father) or quickly change the conversation when the topic of how fashionable Delores (my mother) came up.

I can only hope that they were trying to shield me from hurt, but when it came to discussing my parents death, I always felt alone. I had so many questions about death and dying. Where did they go when they died? How did they split their time between the cemetery and heaven? If they were in heaven why do we keep bringing flowers to this cemetery in New Jersey? My family made frequent visits to my parents’ graves (holidays, birthdays, anniversaries of their death, all the days). That’s how they grieved. I preferred to grieve differently but at 5 I had no platform to voice my concerns. I had no one to talk to.

I spent too much time feeling angry that I didn’t have my own memories of my parents. And the memories that other people had, they seemed to hold onto tightly, rarely sharing them with me. Because I didn’t know everything about them, I felt like I couldn’t love them like everyone else. BIG’s death showed me how diverse groups of people who had birthed him, recorded music with him, mentored him, and some (like me) who had just listened to his music. We all had different relationships with him — but all loved him. I could create my own memories of my parents and love them for that, always.

storybreak-theroot-afropicker");">

I remember the day when people came back to the block after standing on Fulton Street watching the procession of BIG’s hearse through the streets. I was home because I was 7, but I remember people saying “I can’t believe he’s gone.” I felt the sadness and heaviness of my community’s loss in particular; as if I had lost someone. The air was heavy, and people were mad at the West Coast, where I had never been.

The funeral procession of rapper Biggie Smalls passes as mourners line the streets near the building where the slain rapper once lived on St. James Place in the Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn on March 18, 1997.

Photo: AP Photo/Mark Lennihan

I remember watching the news footage of people in the street when they started playing “Hypnotize” to the crowd. I knew that it was okay to celebrate life and what people had given you while they were on earth. I wanted to know what my parents left behind —- where could I find the joy in their existence like people found in Biggie’s songs when Mrs. Wallace returned home to Bed Stuy.

I was never told that crying, or feeling angry, and upset was okay. That these were normal and just reactions to death. People pouring into the streets, crying publicly at award shows and TV interviews showed me that I didn’t need to cry in the closet or the bathroom. That there was nothing to be ashamed of. My pain was valid and all people feel that as a part of life. I was not alone. BIG’s death normalized grief for me.

More than that day, I remember the songs and videos that came out following his death. “I’ll Be Missing You” and “We’ll Always Love Big Poppa” especially because they have children in them. Every time these videos came on, I would stand directly in front of the TV mesmerized, and singing along with Diddy (then Puff Daddy), Faith Evans, and 112. I remember Diddy rapping, “In the future, I can’t wait to see if you’ll open up the gates for me,” and children dressed in all white running into what looked like forever, one of them his daughter Tyanna. Years after Biggie’s death I would think about his children. They were rich but would they be like me, orphans? Biggie’s children, Tyanna was 3 years old and Christopher Wallace Jr. was only 4 months old at the time of their father’s death. Would they remember their father? Have someone to talk to about his death? Did they secretly cry in the bathroom or the closet when they missed him? Learn the word grief before they were in high school?

Less than a month after Biggie’s death, “Life After Death” was released. To me, this was BIG living beyond the grave. It allowed me to move past the memories of my father’s funeral, what those tiny red roses that we placed on his coffin smelled like. My father, my mother, and even BIG had more living to do after the funeral services were over. Every time I heard a song from “Life After Death” I believed that more and more. My parents did not leave me an album to be released posthumously, but they created me. I am my parent’s legacy — I get to be that. I am a living manifestation of their hopes, dreams, and the continuance of their lives here on the earth. I don’t just believe that they are just resting, but rather that they are here resisting, creating joy, and building black futures alongside me and inside me every day.

I loved Notorious BIG, who made music about surviving and thriving despite the odds. That’s what I had to do as a Black girl who lost both of her parents while growing up in Bed Stuy in the 1990s. This would change a little bit after a few women’s studies courses and a deep dive into Joan Morgan’s When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost: My Life as a Hip Hop Feminist, nevertheless, Biggie still has a place on my altar and in my heart today because his death and how the world reacted to it helped me do what I know now is, grieve.

https://www.theroot.com/i-ll-always-love-big-poppa-how-biggie-smalls-helped-me-1823628081