Can AI Unlock the Secrets of the Ancient World?

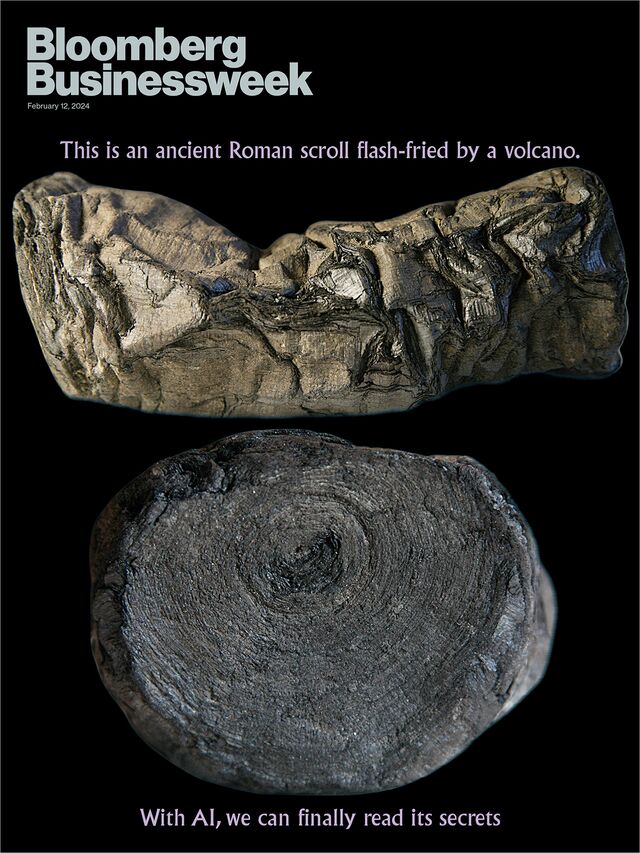

Almost 2,000 years ago, a volcano preserved Herculaneum’s vast library of scrolls in unreadable char. A volunteer army of nerds has been racing to decipher them.

Can AI Unlock the Secrets of the Ancient World?

Almost 2,000 years ago, a volcano preserved Herculaneum’s vast library of scrolls but left them unreadable. A volunteer army of nerds has been racing to decipher them.

By Ashlee Vance and Ellen Huet

February 5, 2024 at 9:00 AM EST

Share this article

Can AI Unlock the Secrets of the Ancient World?

A few years ago, during one of California’s steadily worsening wildfire seasons, Nat Friedman’s family home burned down. A few months after that, Friedman was in Covid-19 lockdown in the Bay Area, both freaked out and bored. Like many a middle-aged dad, he turned for healing and guidance to ancient Rome. While some of us were watching Tiger King and playing with our kids’ Legos, he read books about the empire and helped his daughter make paper models of Roman villas. Instead of sourdough, he learned to bake Panis Quadratus, a Roman loaf pictured in some of the frescoes found in Pompeii. During sleepless pandemic nights, he spent hours trawling the internet for more Rome stuff. That’s how he arrived at the Herculaneum papyri, a fork in the road that led him toward further obsession. He recalls exclaiming: “How the hell has no one ever told me about this?”

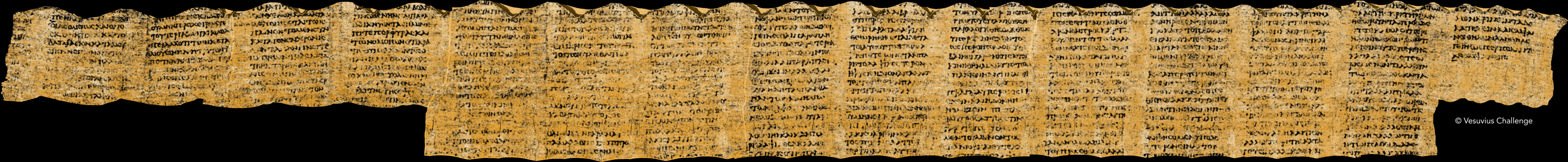

Featured in Bloomberg Businessweek, Feb. 12, 2024. Subscribe now. Photos courtesy Vesuvius Challenge

The Herculaneum papyri are a collection of scrolls whose status among classicists approaches the mythical. The scrolls were buried inside an Italian countryside villa by the same volcanic eruption in 79 A.D. that froze Pompeii in time. To date, only about 800 have been recovered from the small portion of the villa that’s been excavated. But it’s thought that the villa, which historians believe belonged to Julius Caesar’s prosperous father-in-law, had a huge library that could contain thousands or even tens of thousands more. Such a haul would represent the largest collection of ancient texts ever discovered, and the conventional wisdom among scholars is that it would multiply our supply of ancient Greek and Roman poetry, plays and philosophy by manyfold. High on their wish lists are works by the likes of Aeschylus, Sappho and Sophocles, but some say it’s easy to imagine fresh revelations about the earliest years of Christianity.

“Some of these texts could completely rewrite the history of key periods of the ancient world,” says Robert Fowler, a classicist and the chair of the Herculaneum Society, a charity that tries to raise awareness of the scrolls and the villa site. “This is the society from which the modern Western world is descended.”

Friedman (right) and Brent Seales, who’s been working to read the scrolls for 20 years. Photographer: Helynn Ospina for Bloomberg Businessweek

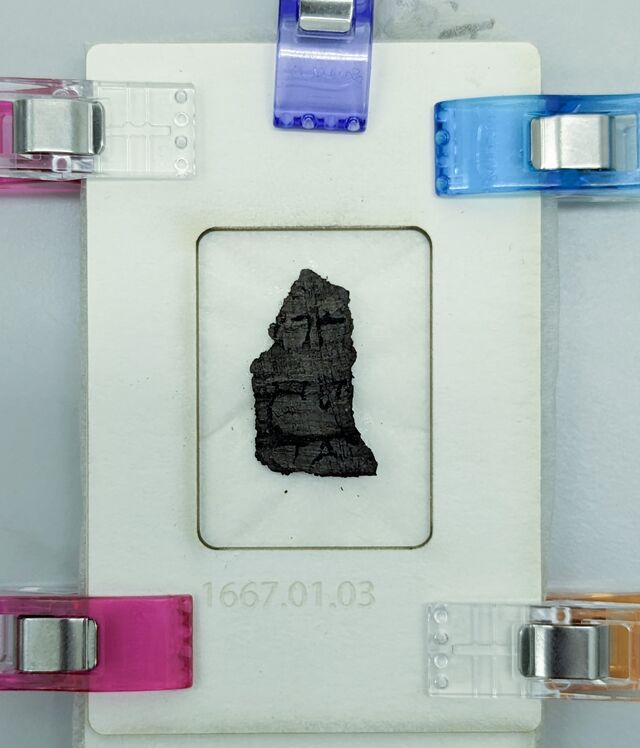

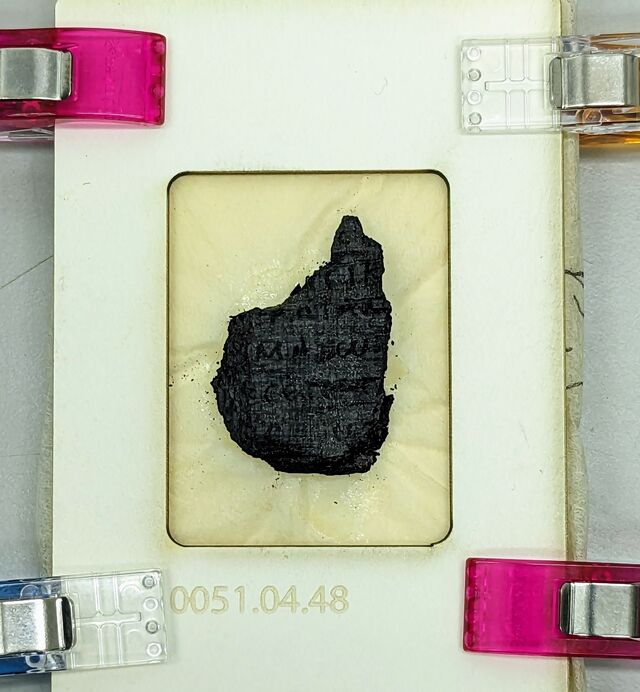

The reason we don’t know exactly what’s in the Herculaneum papyri is, y’know, volcano. The scrolls were preserved by the voluminous amount of superhot mud and debris that surrounded them, but the knock-on effects of Mount Vesuvius charred them beyond recognition. The ones that have been excavated look like leftover logs in a doused campfire. People have spent hundreds of years trying to unroll them—sometimes carefully, sometimes not. And the scrolls are brittle. Even the most meticulous attempts at unrolling have tended to end badly, with them crumbling into ashy pieces.

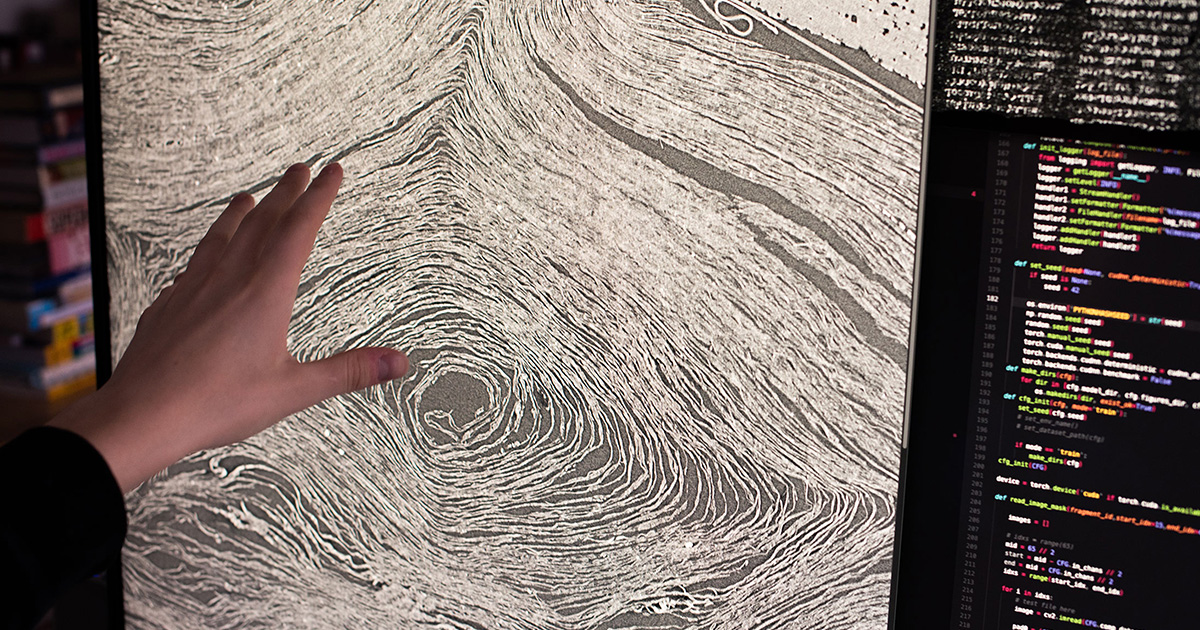

In recent years, efforts have been made to create high-resolution, 3D scans of the scrolls’ interiors, the idea being to unspool them virtually. This work, though, has often been more tantalizing than revelatory. Scholars have been able to glimpse only snippets of the scrolls’ innards and hints of ink on the papyrus. Some experts have sworn they could see letters in the scans, but consensus proved elusive, and scanning the entire cache is logistically difficult and prohibitively expensive for all but the deepest-pocketed patrons. Anything on the order of words or paragraphs has long remained a mystery.

But Friedman wasn’t your average Rome-loving dad. He was the chief executive officer of GitHub Inc., the massive software development platform that Microsoft Corp. acquired in 2018. Within GitHub, Friedman had been developing one of the first coding assistants powered by artificial intelligence, and he’d seen the rising power of AI firsthand. He had a hunch that AI algorithms might be able to find patterns in the scroll images that humans had missed.

After studying the problem for some time and ingratiating himself with the classics community, Friedman, who’s left GitHub to become an AI-focused investor, decided to start a contest. Last year he launched the Vesuvius Challenge, offering $1 million in prizes to people who could develop AI software capable of reading four passages from a single scroll. “Maybe there was obvious stuff no one had tried,” he recalls thinking. “My life has validated this notion again and again.”

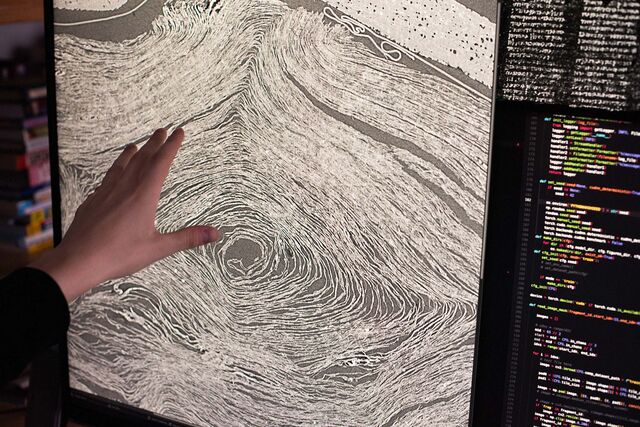

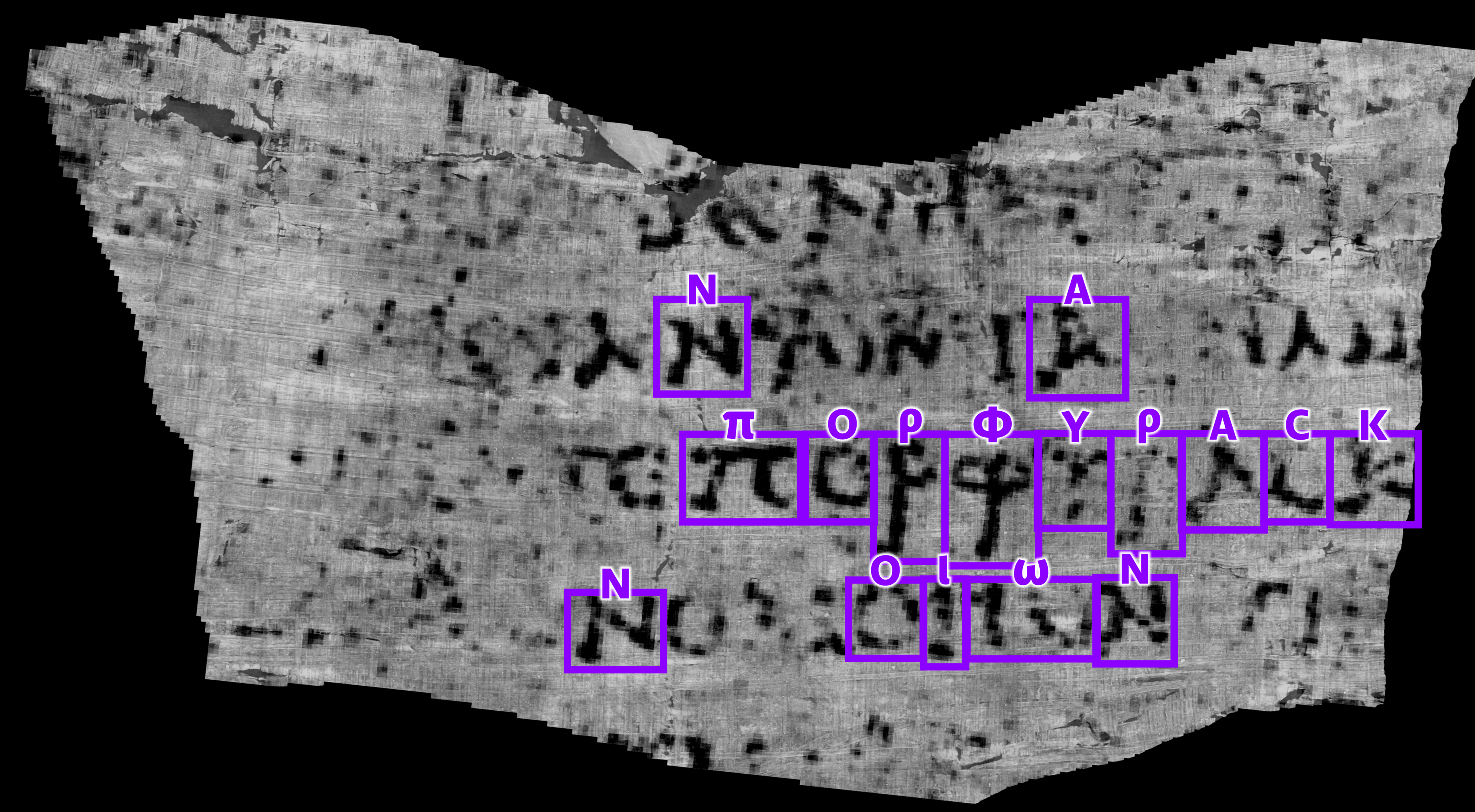

As the months ticked by, it became clear that Friedman’s hunch was a good one. Contestants from around the world, many of them twentysomethings with computer science backgrounds, developed new techniques for taking the 3D scans and flattening them into more readable sheets. Some appeared to find letters, then words. They swapped messages about their work and progress on a Discord chat, as the often much older classicists sometimes looked on in hopeful awe and sometimes slagged off the amateur historians.

On Feb. 5, Friedman and his academic partner Brent Seales, a computer science professor and scroll expert, plan to reveal that a group of contestants has delivered transcriptions of many more than four passages from one of the scrolls. While it’s early to draw any sweeping conclusions from this bit of work, Friedman says he’s confident that the same techniques will deliver far more of the scrolls’ contents. “My goal,” he says, “is to unlock all of them.”

An artist’s rendering of the villa where the scrolls were found. Source: Rocío Espín

Before Mount Vesuvius erupted, the town of Herculaneum sat at the edge of the Gulf of Naples, the sort of getaway wealthy Romans used to relax and think. Unlike Pompeii, which took a direct hit from the Vesuvian lava flow, Herculaneum was buried gradually by waves of ash, pumice and gases. Although the process was anything but gentle, most inhabitants had time to escape, and much of the town was left intact under the hardening igneous rock. Farmers first rediscovered the town in the 18th century, when some well-diggers found marble statues in the ground. In 1750 one of them collided with the marble floor of the villa thought to belong to Caesar’s father-in-law, Senator Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, known to historians today as Piso.

During this time, the first excavators who dug tunnels into the villa to map it were mostly after more obviously valuable artifacts, like the statues, paintings and recognizable household objects. Initially, people who ran across the scrolls, some of which were scattered across the colorful floor mosaics, thought they were just logs and threw them on a fire. Eventually, though, somebody noticed the logs were often found in what appeared to be libraries or reading rooms, and realized they were burnt papyrus. Anyone who tried to open one, however, found it crumbling in their hands.

Terrible things happened to the scrolls in the many decades that followed. The scientif-ish attempts to loosen the pages included pouring mercury on them (don’t do that) and wafting a combination of gases over them (ditto). Some of the scrolls have been sliced in half, scooped out and generally abused in ways that still make historians weep. The person who came the closest in this period was Antonio Piaggio, a priest. In the late 1700s he built a wooden rack that pulled silken threads attached to the edge of the scrolls and could be adjusted with a simple mechanism to unfurl the document ever so gently, at a rate of 1 inch per day. Improbably, it sort of worked; the contraption opened some scrolls, though it tended to damage them or outright tear them into pieces. In later centuries, teams organized by other European powers, including one assembled by Napoleon, pieced together torn bits of mostly illegible text here and there.

You can imagine why trying to just pull one of these open really hard didn’t go well. Courtesy: Vesuvius Challenge

Today the villa remains mostly buried, unexcavated and off-limits even to the experts. Most of what’s been found there and proven legible has been attributed to Philodemus, an Epicurean philosopher and poet, leading historians to hope there’s a much bigger main library buried elsewhere on-site. A wealthy, educated man like Piso would have had the classics of the day along with more modern works of history, law and philosophy, the thinking goes. “I do believe there’s a much bigger library there,” says Richard Janko, a University of Michigan classical studies professor who’s spent painstaking hours assembling scroll fragments by hand, like a jigsaw puzzle. “I see no reason to think it should not still be there and preserved in the same way.” Even an ordinary citizen from that time could have collections of tens of thousands of scrolls, Janko says. Piso is known to have corresponded often with the Roman statesman Cicero, and the apostle Paul had passed through the region a couple of decades before Vesuvius erupted. There could be writings tied to his visit that comment on Jesus and Christianity. “We have about 800 scrolls from the villa today,” Janko says. “There could be thousands or tens of thousands more.”