Beyond gene-edited babies: the possible paths for tinkering with human evolution

CRISPR will get easier and easier to administer. What does that mean for the future of our species?

Biotechnology and health

Beyond gene-edited babies: the possible paths for tinkering with human evolution

CRISPR will get easier and easier to administer. What does that mean for the future of our species?

By

August 22, 2024

Michael Byers

In 2016, I attended a large meeting of journalists in Washington, DC. The keynote speaker was Jennifer Doudna, who just a few years before had co-invented CRISPR, a revolutionary method of changing genes that was sweeping across biology labs because it was so easy to use. With its discovery, Doudna explained, humanity had achieved the ability to change its own fundamental molecular nature. And that capability came with both possibility and danger. One of her biggest fears, she said, was “waking up one morning and reading about the first CRISPR baby”—a child with deliberately altered genes baked in from the start.

As a journalist specializing in genetic engineering—the weirder the better—I had a different fear. A CRISPR baby would be a story of the century, and I worried some other journalist would get the scoop. Gene editing had become the biggest subject on the biotech beat, and once a team in China had altered the DNA of a monkey to introduce customized mutations, it seemed obvious that further envelope-pushing wasn’t far off.

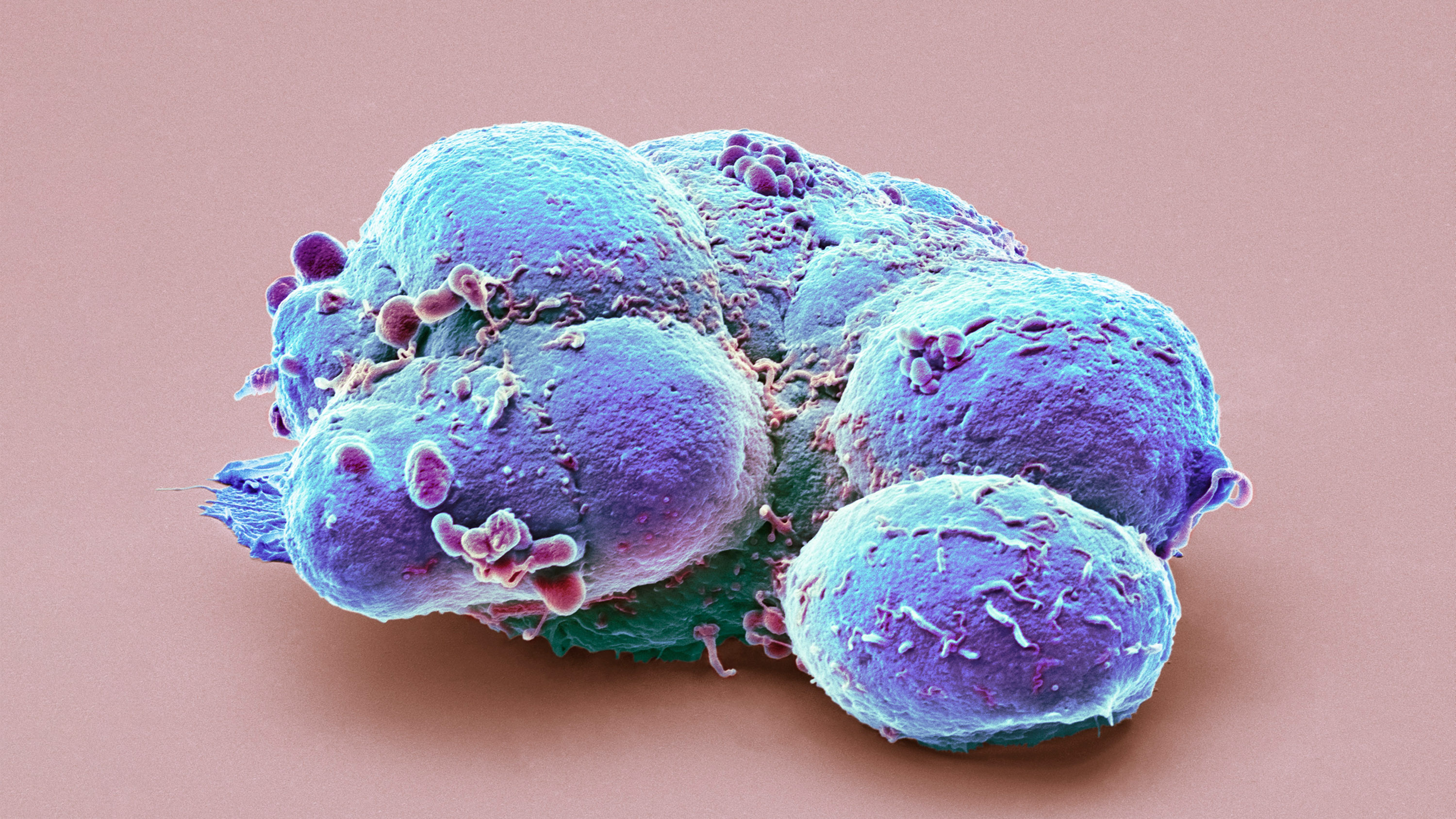

If anyone did create an edited baby, it would raise moral and ethical issues, among the profoundest of which, Doudna had told me, was that doing so would be “changing human evolution.” Any gene alterations made to an embryo that successfully developed into a baby would get passed on to any children of its own, via what’s known as the germline. What kind of scientist would be bold enough to try that?

Two years and nearly 8,000 miles in an airplane seat later, I found the answer. At a hotel in Guangzhou, China, I joined a documentary film crew for a meeting with a biophysicist named He Jiankui, who appeared with a retinue of advisors. During the meeting, He was immensely gregarious and spoke excitedly about his research on embryos of mice, monkeys, and humans, and about his eventual plans to improve human health by adding beneficial genes to people’s bodies from birth. Still imagining that such a step must lie at least some way off, I asked if the technology was truly ready for such an undertaking.

“Ready,” He said. Then, after a laden pause: “Almost ready.”

Why wait 100,000 years for natural selection to do its job? For a few hundred dollars in chemicals, you could try to install these changes in an embryo in 10 minutes.

Four weeks later, I learned that he’d already done it, when I found data that He had placed online describing the genetic profiles of two gene-edited human fetuses—that is, ”CRISPR babies” in gestation—as well an explanation of his plan, which was to create humans immune to HIV. He had targeted a gene called CCR5, which in some people has a variation known to protect against HIV infection. It’s rare for numbers in a spreadsheet to make the hair on your arms stand up, although maybe some climatologists feel the same way seeing the latest Arctic temperatures. It appeared that something historic—and frightening—had already happened. In our story breaking the news that same day, I ventured that the birth of genetically tailored humans would be something between a medical breakthrough and the start of a slippery slope of human enhancement.

For his actions, He was later sentenced to three years in prison, and his scientific practices were roundly excoriated. The edits he made, on what proved to be twin girls (and a third baby, revealed later), had in fact been carelessly imposed, almost in an out-of-control fashion, according to his own data. And I was among a flock of critics—in the media and academia—who would subject He and his circle of advisors to Promethean-level torment via a daily stream of articles and exposés. Just this spring, Fyodor Urnov, a gene-editing specialist at the University of California, Berkeley, lashed out on X, calling He a scientific “pyromaniac” and comparing him to a Balrog, a demon from J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. It could seem as if He’s crime wasn’t just medical wrongdoing but daring to take the wheel of the very processes that brought you, me, and him into being.

Related Story

China’s CRISPR babies: Read exclusive excerpts from the unseen original research

He Jiankui’s manuscript shows how he ignored ethical and scientific norms in creating the gene-edited twins Lulu and Nana.

Futurists who write about the destiny of humankind have imagined all sorts of changes. We’ll all be given auxiliary chromosomes loaded with genetic goodies, or maybe we’ll march through life as a member of a pod of identical clones. Perhaps sex will become outdated as we reproduce exclusively through our stem cells. Or human colonists on another planet will be isolated so long that they become their own species. The thing about He’s idea, though, is that he drew it from scientific realities close at hand. Just as some gene mutations cause awful, rare diseases, others are being discovered that lend a few people the ability to resist common ones, like diabetes, heart disease, Alzheimer’s—and HIV. Such beneficial, superpower-like traits might spread to the rest of humanity, given enough time. But why wait 100,000 years for natural selection to do its job? For a few hundred dollars in chemicals, you could try to install these changes in an embryo in 10 minutes. That is, in theory, the easiest way to go about making such changes—it’s just one cell to start with.

Editing human embryos is restricted in much of the world—and making an edited baby is flatly illegal in most countries surveyed by legal scholars. But advancing technology could render the embryo issue moot. New ways of adding CRISPR to the bodies of people already born—children and adults—could let them easily receive changes as well. Indeed, if you are curious what the human genome could look like in 125 years, it’s possible that many people will be the beneficiaries of multiple rare, but useful, gene mutations currently found in only small segments of the population. These could protect us against common diseases and infections, but eventually they could also yield frank improvements in other traits, such as height, metabolism, or even cognition. These changes would not be passed on genetically to people’s offspring, but if they were widely distributed, they too would become a form of human-directed self-evolution—easily as big a deal as the emergence of computer intelligence or the engineering of the physical world around us.

I was surprised to learn that even as He’s critics take issue with his methods, they see the basic stratagem as inevitable. When I asked Urnov, who helped coin the term “genome editing” in 2005, what the human genome could be like in, say, a century, he readily agreed that improvements using superpower genes will probably be widely introduced into adults—and embryos—as the technology to do so improves. But he warned that he doesn’t necessarily trust humanity to do things the right way. Some groups will probably obtain the health benefits before others. And commercial interests could eventually take the trend in unhelpful directions—much as algorithms keep his students’ noses pasted, unnaturally, to the screens of their mobile phones. “I would say my enthusiasm for what the human genome is going to be in 100 years is tempered by our history of a lack of moderation and wisdom,” he said. “You don’t need to be Aldous Huxley to start writing dystopias.”

Editing early

At around 10 p.m. Beijing time, He’s face flicked into view over the Tencent videoconferencing app. It was May 2024, nearly six years after I had first interviewed him, and he appeared in a loftlike space with a soaring ceiling and a wide-screen TV on a wall. Urnov had warned me not to speak with He, since it would be like asking “Bernie Madoff to opine about ethical investing.” But I wanted to speak to him, because he’s still one of the few scientists willing to promote the idea of broad improvements to humanity’s genes.

Of course, it’s his fault everyone is so down on the idea. After his experiment, China formally made “implantation” of gene-edited human embryos into the uterus a crime. Funding sources evaporated. “He created this blowback, and it brought to a halt many people’s research. And there were not many to begin with,” says Paula Amato, a fertility doctor at Oregon Health and Science University who co-leads one of only two US teams that have ever reported editing human embryos in a lab. “And the publicity—nobody wants to be associated with something that is considered scandalous or eugenic.”

humans dont learn do they...

humans dont learn do they...