ogc163

Superstar

By Ruth Igielnik, Scott Keeter and Hannah Hartig

Steph Smith drops off her ballot for the 2020 presidential election on Nov. 3 in Rollinsville, Colorado. (Jason Connolly/AFP via Getty Images)

How we did this

Pew Research Center conducted this study to understand how Americans voted in 2020 and how their turnout and vote choices differed from 2016 and 2018. For this analysis, we surveyed U.S. adults online and verified their turnout in the three general elections using commercial voter files that aggregate official state turnout records. Panelists for whom a record of voting was located are considered validated voters; all others are presumed not to have voted.

We surveyed 11,818 U.S. adults online in November 2020, 10,640 adults in November 2018 and 4,183 adults in November and December 2016. The surveys were supplemented with measures taken from annual recruitment and profile surveys conducted in 2018 and 2020. Everyone who took part is a member of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel recruited through national, random sampling of telephone numbers or, since 2018, residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The surveys are weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education, turnout and vote choice in the three elections, and many other characteristics. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

Here are the questions used for this report and its methodology.

The 2020 presidential election was historic in many ways. Amid a global pandemic, with unprecedented changes in how Americans voted, voter turnout rose 7 percentage points over 2016, resulting in a total of 66% of U.S. adult citizens casting a ballot in the 2020 election. Joe Biden defeated Donald Trump 306-232 in the Electoral College and had a 4-point margin in the popular vote. While Biden’s popular vote differential was an improvement over Hillary Clinton’s 2016 2-point advantage, it was not as resounding as congressional Democrats’ 9-point advantage over Republicans in votes cast in the 2018 elections for the U.S. House of Representatives.

Validated voters, defined

Members of Pew Research Center’s nationally representative American Trends Panel were matched to public voting records from three national commercial voter files in an attempt to find a record for voting in the 2020 election. Validated voters are citizens who told us in a post-election survey that they voted in the 2020 general election and have a record for voting in a commercial voter file. Nonvoters are citizens who were not found to have a record of voting in any of the voter files or told us they did not vote.

A new analysis of validated 2020 voters from Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel examines change and continuity in the electorate, both of which contributed to Biden’s victory. It looks at how new voters and voters who turned out in one or both previous elections voted in the 2020 presidential election and offers a detailed portrait of the demographic composition and vote choices of the 2020 electorate. It also provides a comparison with findings from our previous studies of the 2016 and 2018 electorates.

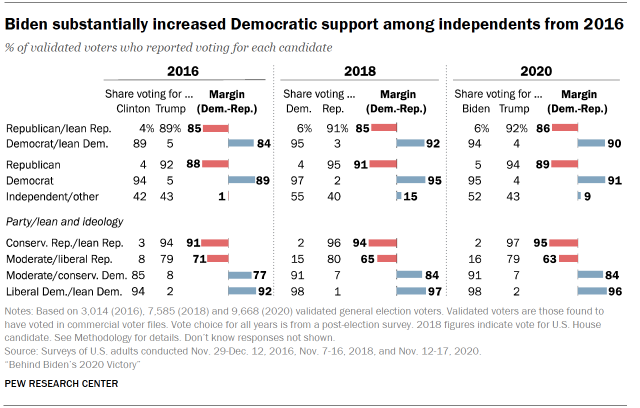

A number of factors determined the composition of the 2020 electorate and explain how it delivered Biden a victory. Among those who voted for Clinton and Trump in 2016, similar shares of each – about nine-in-ten – also turned out in 2020, and the vast majority remained loyal to the same party in the 2020 presidential contest. These voters formed substantial bases of support for both Biden and Trump. Overall, there were shifts in presidential candidate support among some key groups between 2016 and 2020, notably suburban voters and independents. On balance, these shifts helped Biden a little more than Trump.

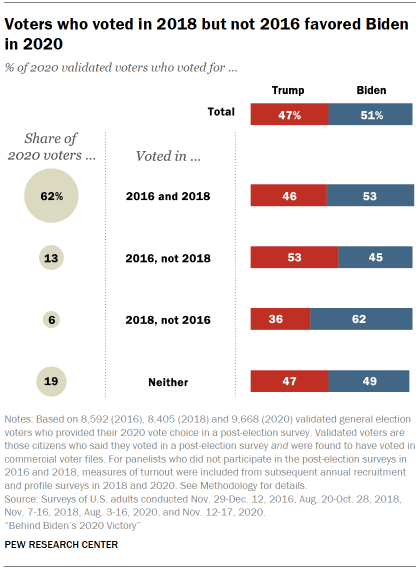

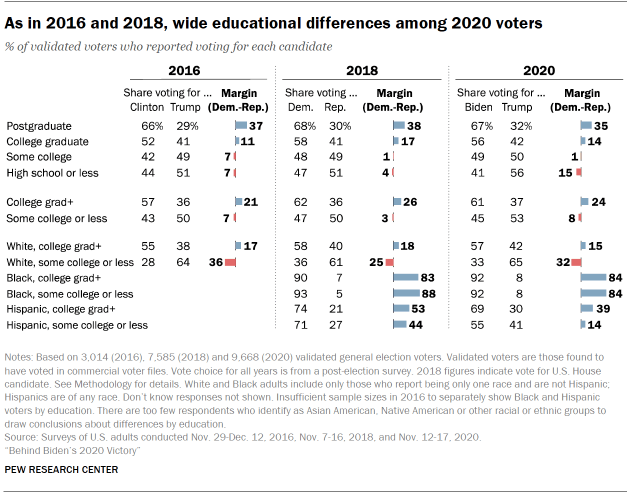

Overall, one-in-four 2020 voters (25%) had not voted in 2016. About a quarter of these (6% of all 2020 voters) showed up two years later – in 2018 – to cast ballots in the highest-turnout midterm election in decades. Those who voted in 2018 but not in 2016 backed Biden over Trump in the 2020 election by about two-to-one (62% to 36%).

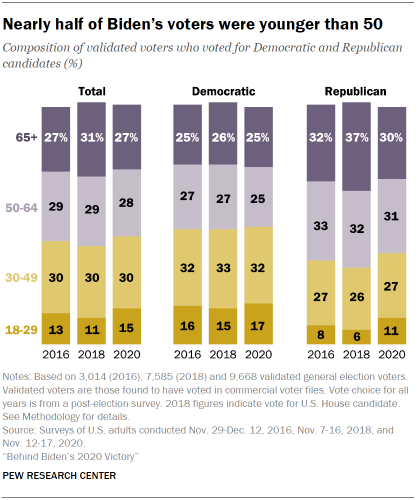

Both Trump and Biden were able to bring new voters into the political process in 2020. The 19% of 2020 voters who did not vote in 2016 or 2018 split roughly evenly between the two candidates (49% Biden vs. 47% Trump). However, as with voters overall, there was a substantial age divide within this group. Among those under age 30 who voted in 2020 but not in either of the two previous elections, Biden led 59% to 33%, while Trump won among new or irregular voters ages 30 and older by 55% to 42%. Younger voters also made up an outsize share of these voters: Those under age 30 made up 38% of new or irregular 2020 voters, though they represented just 15% of all 2020 voters.

One somewhat unusual aspect of the 2016 election was the relatively high share of voters (nearly 6%) who voted for one of the third-party candidates (mostly the Libertarian and Green Party nominees), a fact many observers attributed to the relative unpopularity of both major party candidates. By comparison, just 2% of voters chose a third-party candidate in 2020. Overall, third-party 2016 voters who turned out in 2020 voted 53%-36% for Biden over Trump, with 10% opting for a third-party candidate. Among the 5% of Republicans who voted third-party in 2016 and voted in 2020, a majority (70%) supported Trump in 2020, but 18% backed Biden. Among the 5% of Democrats who voted third-party in 2016 and voted in 2020, just 8% supported Trump in 2020 while 85% voted for Biden.

Here are some of the other key findings from the analysis:

This study marries official turnout records with a post-election survey among a large, ongoing survey panel, with the goal of improving the accuracy of the results compared with relying on self-reported turnout alone. The survey panel also makes it possible to examine change in turnout and vote preference over time among many of the same individuals. This analysis joins a growing body of research seeking to achieve a more accurate assessment of the 2020 election, each based on somewhat different sources of data. Different methods and data sources have unique strengths and weaknesses, meaning that specific estimates are likely to vary among the studies and no single resource can be considered definitive.

Steph Smith drops off her ballot for the 2020 presidential election on Nov. 3 in Rollinsville, Colorado. (Jason Connolly/AFP via Getty Images)

How we did this

Pew Research Center conducted this study to understand how Americans voted in 2020 and how their turnout and vote choices differed from 2016 and 2018. For this analysis, we surveyed U.S. adults online and verified their turnout in the three general elections using commercial voter files that aggregate official state turnout records. Panelists for whom a record of voting was located are considered validated voters; all others are presumed not to have voted.

We surveyed 11,818 U.S. adults online in November 2020, 10,640 adults in November 2018 and 4,183 adults in November and December 2016. The surveys were supplemented with measures taken from annual recruitment and profile surveys conducted in 2018 and 2020. Everyone who took part is a member of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel recruited through national, random sampling of telephone numbers or, since 2018, residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The surveys are weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education, turnout and vote choice in the three elections, and many other characteristics. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

Here are the questions used for this report and its methodology.

The 2020 presidential election was historic in many ways. Amid a global pandemic, with unprecedented changes in how Americans voted, voter turnout rose 7 percentage points over 2016, resulting in a total of 66% of U.S. adult citizens casting a ballot in the 2020 election. Joe Biden defeated Donald Trump 306-232 in the Electoral College and had a 4-point margin in the popular vote. While Biden’s popular vote differential was an improvement over Hillary Clinton’s 2016 2-point advantage, it was not as resounding as congressional Democrats’ 9-point advantage over Republicans in votes cast in the 2018 elections for the U.S. House of Representatives.

Validated voters, defined

Members of Pew Research Center’s nationally representative American Trends Panel were matched to public voting records from three national commercial voter files in an attempt to find a record for voting in the 2020 election. Validated voters are citizens who told us in a post-election survey that they voted in the 2020 general election and have a record for voting in a commercial voter file. Nonvoters are citizens who were not found to have a record of voting in any of the voter files or told us they did not vote.

A new analysis of validated 2020 voters from Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel examines change and continuity in the electorate, both of which contributed to Biden’s victory. It looks at how new voters and voters who turned out in one or both previous elections voted in the 2020 presidential election and offers a detailed portrait of the demographic composition and vote choices of the 2020 electorate. It also provides a comparison with findings from our previous studies of the 2016 and 2018 electorates.

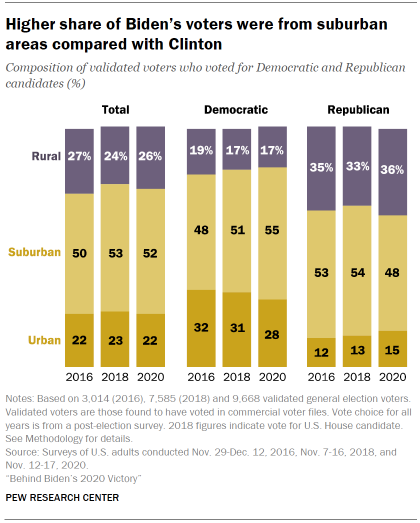

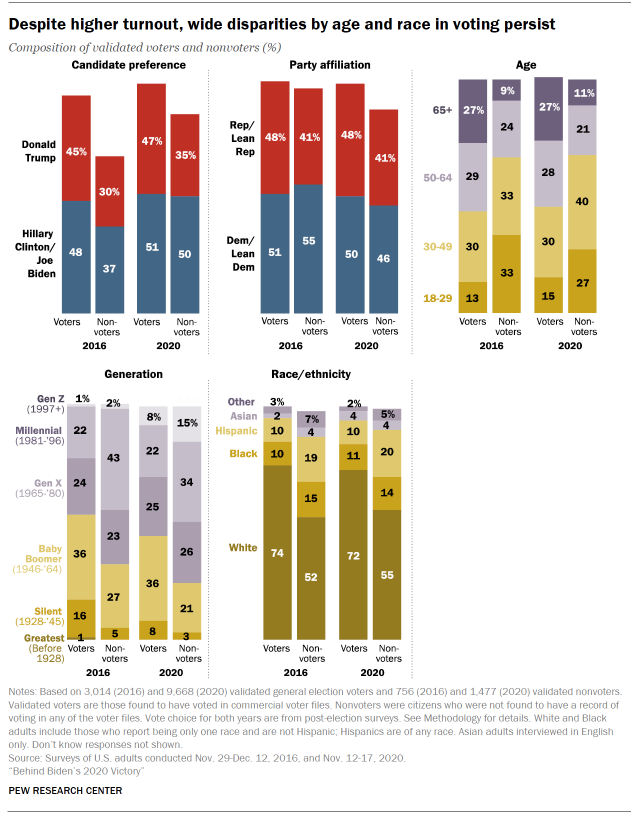

A number of factors determined the composition of the 2020 electorate and explain how it delivered Biden a victory. Among those who voted for Clinton and Trump in 2016, similar shares of each – about nine-in-ten – also turned out in 2020, and the vast majority remained loyal to the same party in the 2020 presidential contest. These voters formed substantial bases of support for both Biden and Trump. Overall, there were shifts in presidential candidate support among some key groups between 2016 and 2020, notably suburban voters and independents. On balance, these shifts helped Biden a little more than Trump.

Overall, one-in-four 2020 voters (25%) had not voted in 2016. About a quarter of these (6% of all 2020 voters) showed up two years later – in 2018 – to cast ballots in the highest-turnout midterm election in decades. Those who voted in 2018 but not in 2016 backed Biden over Trump in the 2020 election by about two-to-one (62% to 36%).

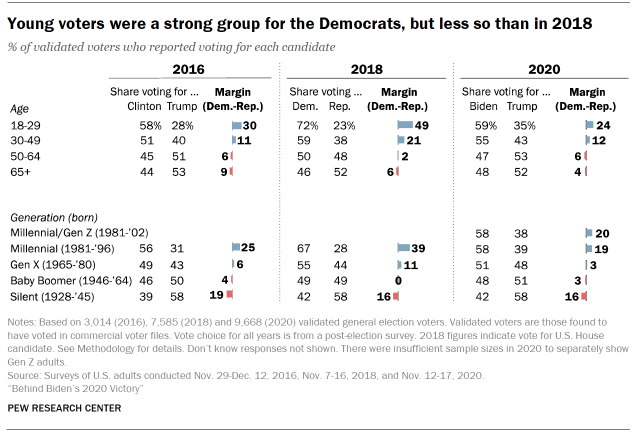

Both Trump and Biden were able to bring new voters into the political process in 2020. The 19% of 2020 voters who did not vote in 2016 or 2018 split roughly evenly between the two candidates (49% Biden vs. 47% Trump). However, as with voters overall, there was a substantial age divide within this group. Among those under age 30 who voted in 2020 but not in either of the two previous elections, Biden led 59% to 33%, while Trump won among new or irregular voters ages 30 and older by 55% to 42%. Younger voters also made up an outsize share of these voters: Those under age 30 made up 38% of new or irregular 2020 voters, though they represented just 15% of all 2020 voters.

One somewhat unusual aspect of the 2016 election was the relatively high share of voters (nearly 6%) who voted for one of the third-party candidates (mostly the Libertarian and Green Party nominees), a fact many observers attributed to the relative unpopularity of both major party candidates. By comparison, just 2% of voters chose a third-party candidate in 2020. Overall, third-party 2016 voters who turned out in 2020 voted 53%-36% for Biden over Trump, with 10% opting for a third-party candidate. Among the 5% of Republicans who voted third-party in 2016 and voted in 2020, a majority (70%) supported Trump in 2020, but 18% backed Biden. Among the 5% of Democrats who voted third-party in 2016 and voted in 2020, just 8% supported Trump in 2020 while 85% voted for Biden.

Here are some of the other key findings from the analysis:

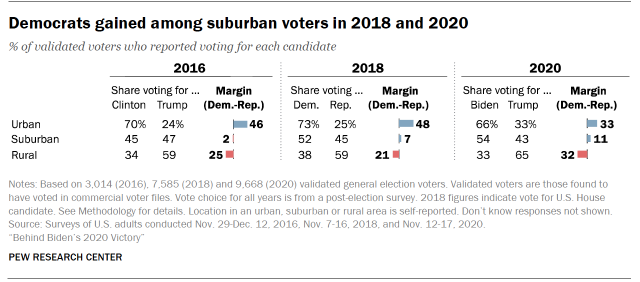

- Biden made gains with suburban voters. In 2020, Biden improved upon Clinton’s vote share with suburban voters: 45% supported Clinton in 2016 vs. 54% for Biden in 2020. This shift was also seen among White voters: Trump narrowly won White suburban voters by 4 points in 2020 (51%-47%); he carried this group by 16 points in 2016 (54%-38%). At the same time, Trump grew his vote share among rural voters. In 2016, Trump won 59% of rural voters, a number that rose to 65% in 2020.

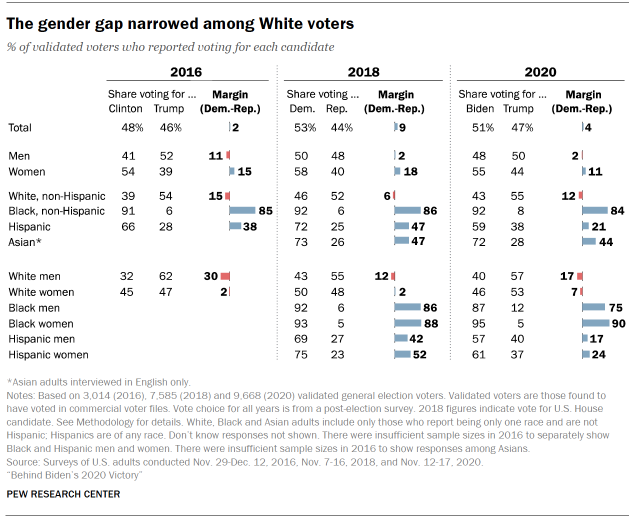

- Trump made gains among Hispanic voters. Even as Biden held on to a majority of Hispanic voters in 2020, Trump made gains among this group overall. There was a wide educational divide among Hispanic voters: Trump did substantially better with those without a college degree than college-educated Hispanic voters (41% vs. 30%).

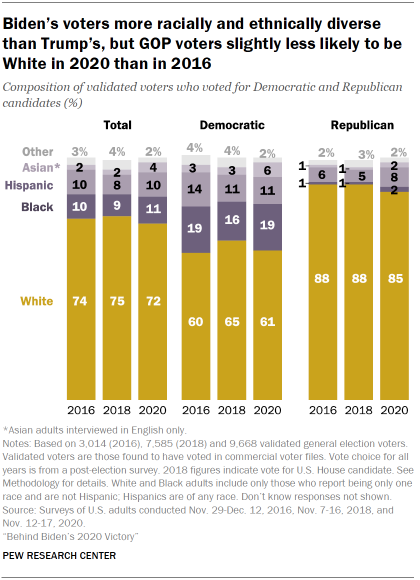

- Apart from the small shift among Hispanic voters, Joe Biden’s electoral coalition looked much like Hillary Clinton’s, with Black, Hispanic and Asian voters and those of other races casting about four-in-ten of his votes. Black voters remained overwhelmingly loyal to the Democratic Party, voting 92%-8% for Biden.

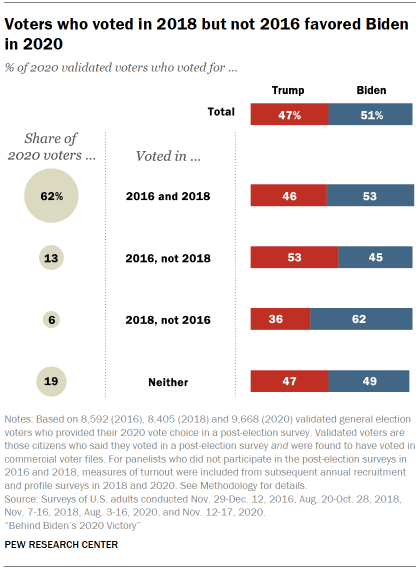

- Biden made gains with men, while Trump improved among women, narrowing the gender gap. The gender gap in the 2020 election was narrower than it had been in 2016, both because of gains that Biden made among men and because of gains Trump made among women. In 2020, men were almost evenly divided between Trump and Biden, unlike in 2016 when Trump won men by 11 points. Trump won a slightly larger share of women’s votes in 2020 than in 2016 (44% vs. 39%), while Biden’s share among women was nearly identical to Clinton’s (55% vs. 54%).

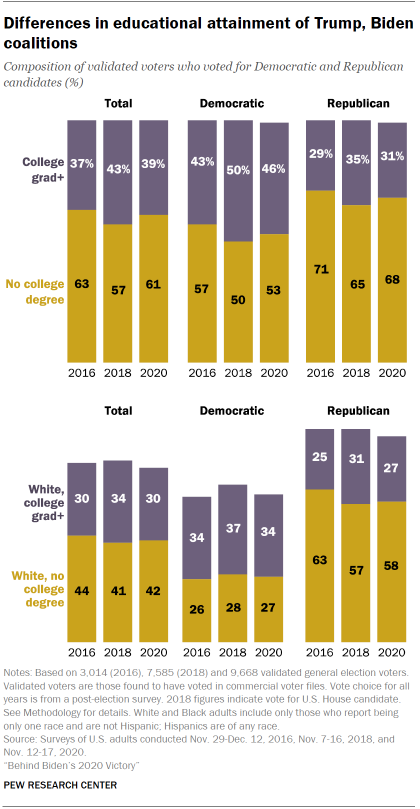

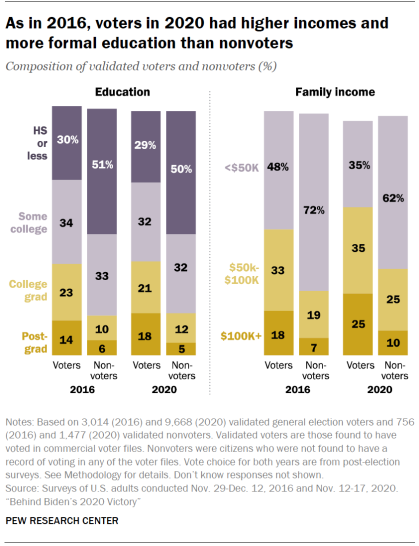

- Biden improved over Clinton among White non-college voters. White voters without a college degree were critical to Trump’s victory in 2016, when he won the group by 64% to 28%. In 2018, Democrats were able to gain some ground with these voters, earning 36% of the White, non-college vote to Republicans’ 61%. In 2020, Biden roughly maintained Democrats’ 2018 share among the group, improving upon Clinton’s 2016 performance by receiving the votes of 33%. But Trump’s share of the vote among this group – who represented 42% of the total electorate this year – was nearly identical to his vote share in 2016 (65%).

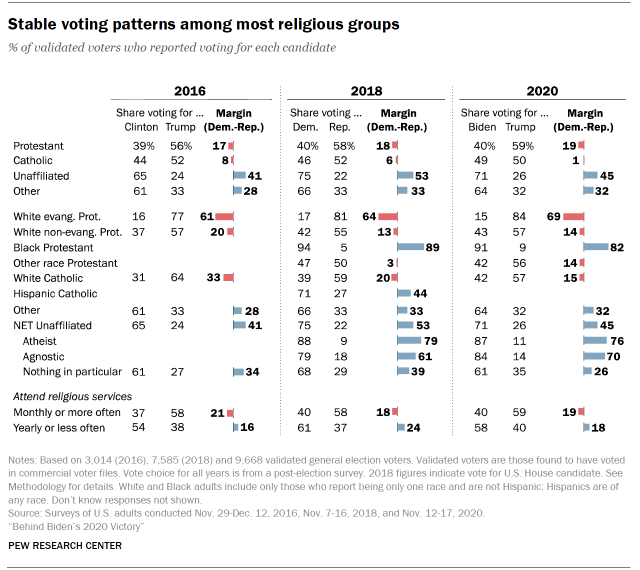

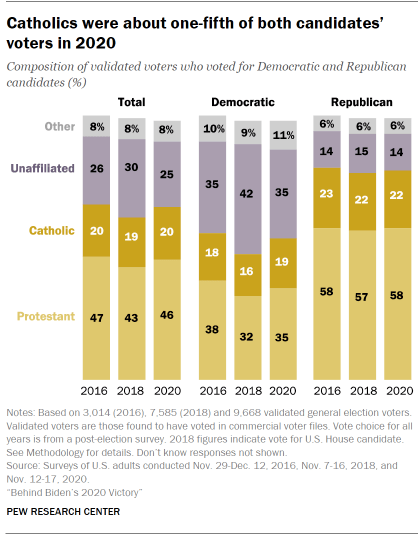

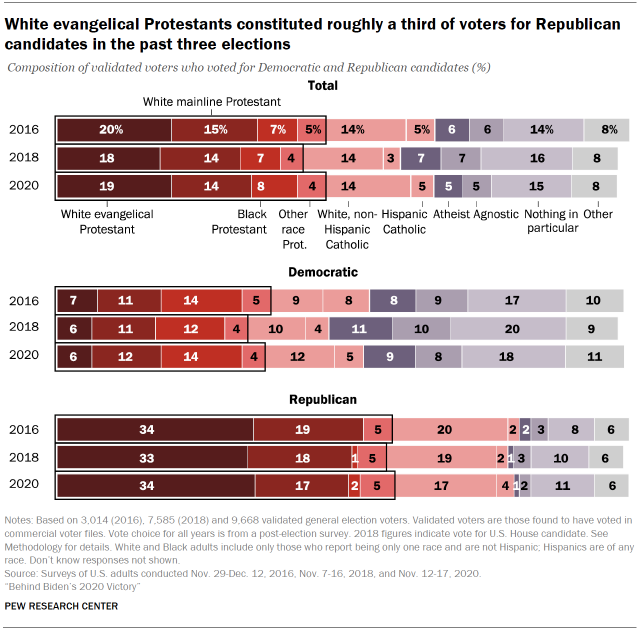

- Biden grew his support with some religious groups while Trump held his ground. Both Trump and Biden held onto or gained with large groups within their respective religious coalitions. Trump’s strong support among White evangelical Protestants ticked up (77% in 2016, 84% in 2020) while Biden got more support among atheists and agnostics than did Clinton in 2016.

- After decades of constituting the majority of voters, Baby Boomers and members of the Silent Generation made up less than half of the electorate in 2020 (44%), falling below the 52% they constituted in both 2016 and 2018. Gen Z and Millennial voters favored Biden over Trump by margins of about 20 points, while Gen Xers and Boomers were more evenly split in their preferences. Gen Z voters, those ages 23 and younger, constituted 8% of the electorate, while Millennials and Gen Xers made up 47% of 2020 voters.

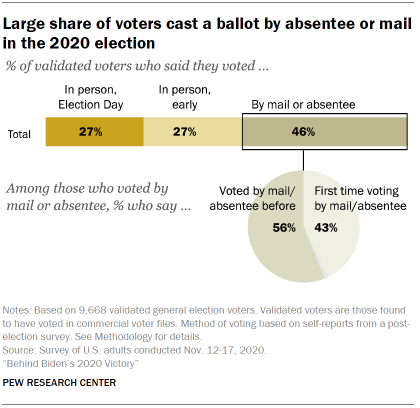

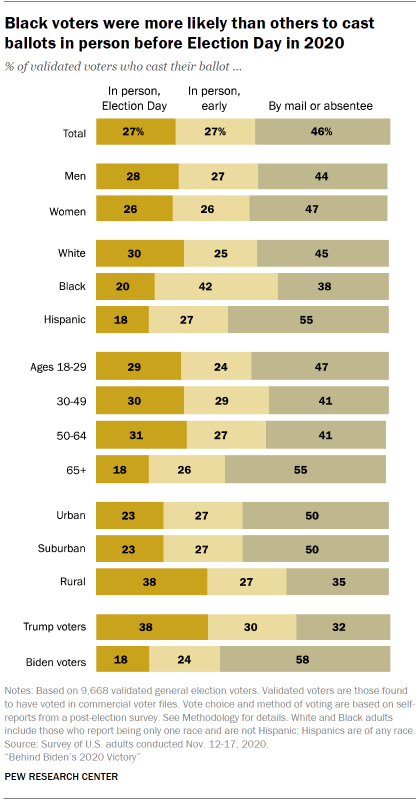

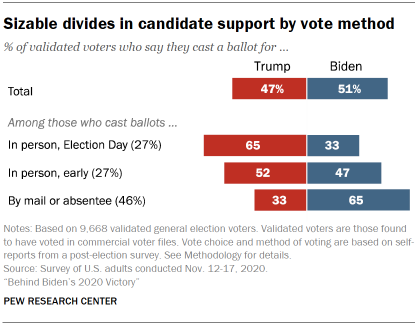

- A record number of voters reported casting ballots by mail in 2020 – including many voters who said it was their first time doing so. Nearly half of 2020 voters (46%) said they had voted by mail or absentee, and among that group, about four-in-ten said it was their first time casting a ballot this way. Hispanic and White voters were more likely than Black voters to have cast absentee or mail ballots, while Black voters were more likely than White or Hispanic voters to have voted early in person. Urban and suburban voters were also more likely than rural voters to have voted absentee or by mail ballot.

This study marries official turnout records with a post-election survey among a large, ongoing survey panel, with the goal of improving the accuracy of the results compared with relying on self-reported turnout alone. The survey panel also makes it possible to examine change in turnout and vote preference over time among many of the same individuals. This analysis joins a growing body of research seeking to achieve a more accurate assessment of the 2020 election, each based on somewhat different sources of data. Different methods and data sources have unique strengths and weaknesses, meaning that specific estimates are likely to vary among the studies and no single resource can be considered definitive.

Don't muck up the thread with that cornball Bernie bro sh*t

Don't muck up the thread with that cornball Bernie bro sh*t

You deadass think this is clever beloved? Did you have a smirk on your face when you clicked Post Reply?

You deadass think this is clever beloved? Did you have a smirk on your face when you clicked Post Reply?