The earthquake that rocked Haiti in 2010 had a devastating impact on the country, destroying much of its infrastructure and leaving many homeless. Its impact on Haitian architecture was significant, particularly in the capital, Port-au-Prince, although other areas of the country reported little damage. As a result, many of its most significant historic buildings remain, serving as blueprints for maintaining a legacy of Haitian architecture in the future.

Colonial Haitian Architecture

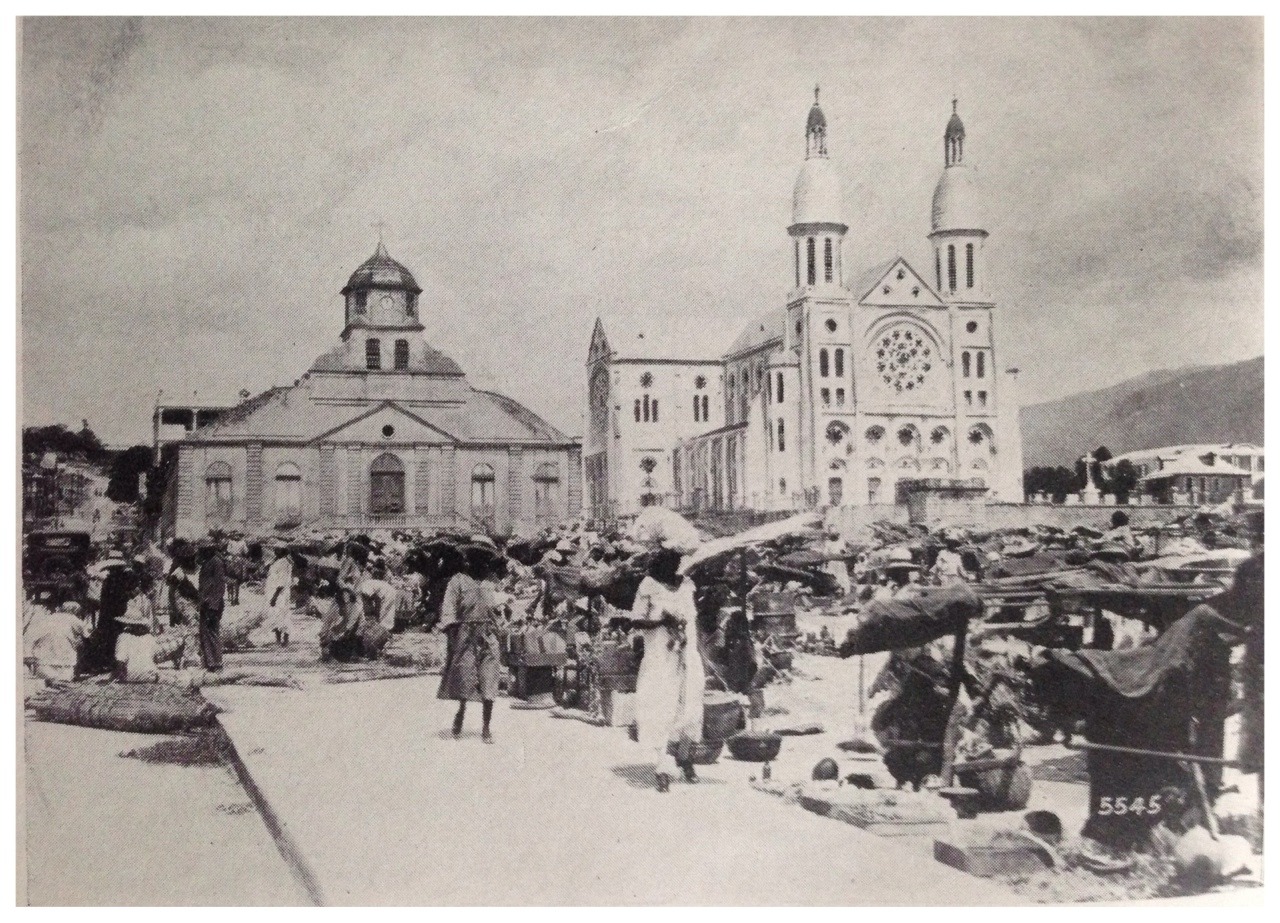

Many of Haiti’s towns and cities feature elegant colonial government buildings and cathedrals which were built during the years of French rule (1625–1804). Cap‑Haïtien which served as the former administrative center is particularly noted for its colonial architecture, including the well-preserved Cathedral Notre-Dame which dates to 1670. It was here in the square that the liberation of Haiti’s slaves was proclaimed on the 29 of August 1793.

Cap‑Haïtien’s infrastructure was not nearly as affected by the 2010 earthquake as Port-au-Prince and it served as the main hub for the distribution of relief supplies in the wake of the disaster.

19th Century Haitian Architecture

Fort Jacques

Fort Jacques, which overlooks the bay of Port-au-Prince, only suffered minor damage in the earthquake and stands as one of the country’s most impressive early 19th century architectural landmarks. It was built between 1804 and 1806 by General Alexandre Petion following Haiti’s independence from France.

Its thick stone, corner bastions, cannons and bombards were designed to deter French troops and it was named in honor of the Haitian Revolution’s leader, Jean-Jacques Dessalines. General Alexandre Petion also supervised the building of Fort Alexandre which is situated a short walk away, but it was abandoned after the death of Jean-Jacques Dessalines in 1806 and today lies in ruins.

Fort Jacques is accessed via a trail which winds through pine forest and is a photogenic spot to soak up this significant part of Haiti’s history. If you’re visiting in May during the anniversary of the Haitian flag’s creation, both Fort Jacques and Fort Alexandre come to life with music and fairs as locals make a pilgrimage here to celebrate.

Citadelle Laferrière

Perhaps Haiti’s most impressive piece of architecture is the Citadelle Laferrière which lies in the north of the country and stands as one of the Americas largest fortresses. It was built by King Henry Christophe on top of Bonnet a L’Eveque mountain between 1805 and 1820 to deter attacks in the years after Haiti gained its independence from France.

Citadelle Laferrière has been designated by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, with its impressive stone structure built by around 20,000 workers. It includes 365 cannons gifted by nations across the world, many of which still bear the crests of 18th century monarchs. Its foundations were built directly into the stone of the mountain using a mortar of quicklime, molasses and the blood of cows and goats, while its angular structure is believed to have been purposefully designed to deflect cannonball shots.

Large cisterns and storehouses were created to store food and water for around 5,000 defenders and the complex includes quarters for the king and his family if they needed to seek refuge, together with dungeons, bath houses and large bakeries.

Piles of cannonballs still sit at the base of the fortress walls, although it’s been earthquakes (rather than French attacks) which have been the most threatening to its survival.

Despite numerous earthquakes and tremors, Citadelle Laferrière still stands and although it has been refurbished and repaired over the years, its original design has been retained. Today it’s one of Haiti’s most important tourist attractions and is featured on Haitian currency and stamps. On a clear day there are views across to Cap-Haïtien from its historic stone fortifications, as well as Cuba which lies around 90 miles to the west.

San-Souci Palace

Sans-Souci Palace in the nearby town of Milot is also UNESCO World Heritage-listed, having served as the most important royal residence for King Henri Christophe. It was built between 1810 and 1813, with its name translating from French as “carefree”.

While today San-Souci Palace is an empty ruin, in its day it featured opulent gardens, artificial springs and an extensive waterworks system, with “the reputation of having been one of the most magnificent edifices of the West Indies”. Henri wanted to demonstrate to foreigners the powers and capabilities of the black race, with his advisor, Pompée Valentin Vastey, quoted as having said it was “erected by descendants of Africans, showing that we have not lost the architectural taste and genius of our ancestors who covered Ethiopia, Egypt, Carthage, and old Spain with their superb monuments.”

King Henri Christophe committed suicide in 1820 (with legend stating that it was a silver bullet to the head) and an earthquake in 1842 largely destroyed the palace. It was never rebuilt, but it is still considered one of the country’s most remarkable attractions and a surviving legacy of 19th century Haitian architecture.

Gingerbread Houses

A distinct Haitian architecture which has captivated countless visitors to the country are the so-called “Gingerbread Houses” – a term which was coined by American tourists in the 1950s. The style originated in the late-19th century with the Haitian National Palace and was inspired by Parisian architecture, although significantly modified for the Caribbean climate and aesthetics.

Gingerbread Houses were usually built of wood and masonry or stone and clay and featured steep turret roofs to redirect hot air and wraparound balconies. They were usually designed with louvered shutter windows to take advantage of the breezes and flexible timber frames to withstand earth tremors and storms, then painted in vibrant colors.

Only around 5% of Gingerbread Houses were destroyed or damaged during the 2010 earthquake (compared to around 40% of other infrastructures) which has left conservation experts thinking that they could serve as a model for seismic-resistant architecture in the future.

Modern and Post-Earthquake Haitian Architecture

Due to a lack of available timber, modern Haitian architecture has largely relied on cheap and durable concrete to build dwellings, with thousands of tons imported to the island each year. The majority of concrete used is in the form of blocks which are often combined with traditional stonework. In the countryside, many of these dwellings are whitewashed or painted in bright colors, with roofs of locally-sourced thick palm thatch.

As Haiti rebuilds in the post-earthquake years, the challenge lies in creating structures and dwellings that will survive future natural disasters, while being accessible to the country’s low-income communities. The infrastructure which remains following this devastating natural disaster not preserve Haitian architectural traditions, but may be key in designing buildings which will stand strong in the future.