Ageing research: Blood to blood

By splicing animals together, scientists have shown that young blood rejuvenates old tissues. Now, they are testing whether it works for humans.

Illustration by Gary Neill

Two mice perch side by side, nibbling a food pellet. As one turns to the left, it becomes clear that food is not all that they share — their front and back legs have been cinched together, and a neat row of sutures runs the length of their bodies, connecting their skin. Under the skin, however, the animals are joined in another, more profound way: they are pumping each other's blood.

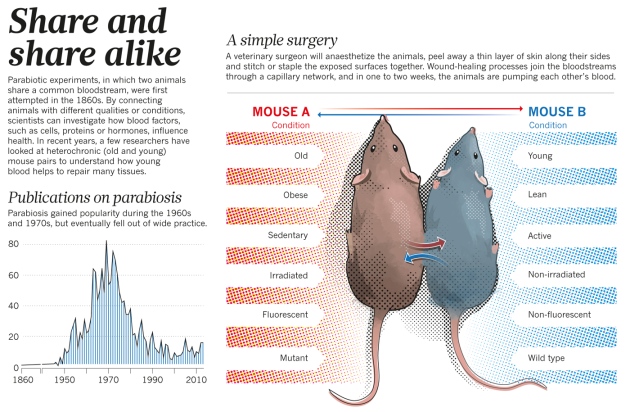

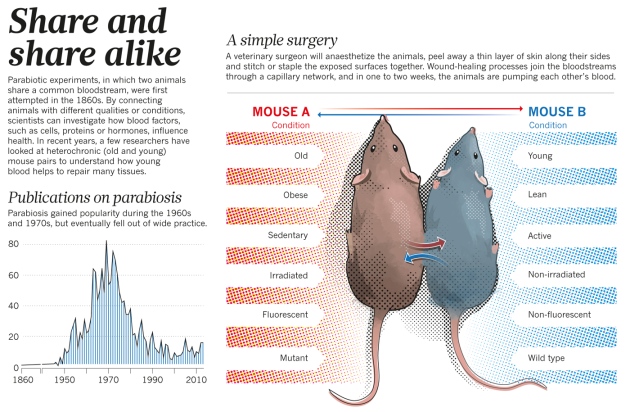

Parabiosis is a 150-year-old surgical technique that unites the vasculature of two living animals. (The word comes from the Greekpara, meaning 'alongside', and bios, meaning 'life'.) It mimics natural instances of shared blood supply, such as in conjoined twins or animals that share a placenta in the womb.

In the lab, parabiosis presents a rare opportunity to test what circulating factors in the blood of one animal do when they enter another animal. Experiments with parabiotic rodent pairs have led to breakthroughs in endocrinology, tumour biology and immunology, but most of those discoveries occurred more than 35 years ago. For reasons that are not entirely clear, the technique fell out of favour after the 1970s.

In the past few years, however, a small number of labs have revived parabiosis, especially in the field of ageing research. By joining the circulatory system of an old mouse to that of a young mouse, scientists have produced some remarkable results. In the heart, brain, muscles and almost every other tissue examined, the blood of young mice seems to bring new life to ageing organs, making old mice stronger, smarter and healthier. It even makes their fur shinier. Now these labs have begun to identify the components of young blood that are responsible for these changes. And last September, a clinical trial in California became the first to start testing the benefits of young blood in older people with Alzheimer's disease.

“I think it is rejuvenation,” says Tony Wyss-Coray, a neurologist at Stanford University in California who founded a company that is running the trial. “We are restarting the ageing clock.”

Many of his colleagues are more cautious about making such claims. “We're not de-ageing animals,” says Amy Wagers, a stem-cell researcher at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, who has identified a muscle-rejuvenating factor in young mouse blood. Wagers argues that such factors are not turning old tissues into young ones, but are instead helping them to repair damage. “We're restoring function to tissues.”

She emphasizes that no one has convincingly shown that young blood lengthens lives, and there is no promise that it will. Still, she says that young blood, or factors from it, may hold promise for helping elderly people to heal after surgery, or treating diseases of ageing.

“It's very provocative,” says Mark Mattson, chief of the Laboratory of Neurosciences at the US National Institute on Aging in Bethesda, Maryland, who has not been involved in the parabiosis work. “It makes you think. Maybe I should bank some blood of my daughter's son, so if I start to have any cognitive problems, I'll have some help,” he says, only half-joking.

The power of two

Physiologist Paul Bert performed the earliest recorded parabiosis experiment in 1864, when he removed a strip of skin from the flanks of two albino rats, then stitched the animals together in hopes of creating a shared circulatory system1. Biology did the rest: natural wound-healing processes joined the animals' circulatory systems as capillaries regrew at the intersection. Bert found that fluid injected into a vein of one rat passed easily into the other, work that won him an award from the French Academy of Sciences in 1866.

Since Bert's initial experiments, the procedure has not changed much. It has been performed on hydra — small freshwater invertebrates related to jellyfish — frogs and insects, but it works best on rodents, which recover well from the surgery. Up to the mid-twentieth century, scientists used parabiotic pairs of mice or rats to study a variety of phenomena. For example, one team ruled out the idea that dental cavities are the result of sugar in the blood by using a pair of parabiosed rats, of which only one was fed a daily diet of glucose. The rats had similar blood glucose levels owing to their shared circulation, yet only the rat that actually ate the sugar developed cavities2.

Nik Spencer/Nature; Chart Data: A. Eggel & T. Wyss-Coray Swiss Med. Wkly 144, W13914 (2014)

3. The linked rats included a 1.5-month-old paired with a 16-month-old — the equivalent of pairing a 5-year-old human with a 47-year-old. It was not a pretty experiment. “If two rats are not adjusted to each other, one will chew the head of the other until it is destroyed,” the authors wrote in one description of their work4. And of the 69 pairs, 11 died from a mysterious condition termed parabiotic disease, which occurs approximately one to two weeks after partners are joined, and may be a form of tissue rejection.

Today, parabiosis is performed carefully to reduce animal discomfort and mortality. “We observe the mice at length and have long discussions with our animal-care committee,” says Thomas Rando, a Stanford neurologist who has used the procedure. “We don't take this lightly.” Mice of the same sex and size are socialized with each other for two weeks before attachment, and the surgery itself is done in a sterile setting with anaesthesia, heating pads and antibiotics to prevent infection. Using inbred lab mice, genetically matched to one another, seems to reduce the risk of parabiotic disease. Joined mice eat, drink and behave normally — and they can be separated successfully.

In McCay's first parabiotic ageing experiment, after old and young rats were joined for 9–18 months, the older animals' bones became similar in weight and density to the bones of their younger counterparts5. More than 15 years later, in 1972, two researchers at the University of California studied the lifespans of old–young rat pairs. Older partners lived for four to five months longer than controls, suggesting for the first time that circulation of young blood might affect longevity6.

By splicing animals together, scientists have shown that young blood rejuvenates old tissues. Now, they are testing whether it works for humans.

Illustration by Gary Neill

Two mice perch side by side, nibbling a food pellet. As one turns to the left, it becomes clear that food is not all that they share — their front and back legs have been cinched together, and a neat row of sutures runs the length of their bodies, connecting their skin. Under the skin, however, the animals are joined in another, more profound way: they are pumping each other's blood.

Parabiosis is a 150-year-old surgical technique that unites the vasculature of two living animals. (The word comes from the Greekpara, meaning 'alongside', and bios, meaning 'life'.) It mimics natural instances of shared blood supply, such as in conjoined twins or animals that share a placenta in the womb.

In the lab, parabiosis presents a rare opportunity to test what circulating factors in the blood of one animal do when they enter another animal. Experiments with parabiotic rodent pairs have led to breakthroughs in endocrinology, tumour biology and immunology, but most of those discoveries occurred more than 35 years ago. For reasons that are not entirely clear, the technique fell out of favour after the 1970s.

In the past few years, however, a small number of labs have revived parabiosis, especially in the field of ageing research. By joining the circulatory system of an old mouse to that of a young mouse, scientists have produced some remarkable results. In the heart, brain, muscles and almost every other tissue examined, the blood of young mice seems to bring new life to ageing organs, making old mice stronger, smarter and healthier. It even makes their fur shinier. Now these labs have begun to identify the components of young blood that are responsible for these changes. And last September, a clinical trial in California became the first to start testing the benefits of young blood in older people with Alzheimer's disease.

“I think it is rejuvenation,” says Tony Wyss-Coray, a neurologist at Stanford University in California who founded a company that is running the trial. “We are restarting the ageing clock.”

Many of his colleagues are more cautious about making such claims. “We're not de-ageing animals,” says Amy Wagers, a stem-cell researcher at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, who has identified a muscle-rejuvenating factor in young mouse blood. Wagers argues that such factors are not turning old tissues into young ones, but are instead helping them to repair damage. “We're restoring function to tissues.”

She emphasizes that no one has convincingly shown that young blood lengthens lives, and there is no promise that it will. Still, she says that young blood, or factors from it, may hold promise for helping elderly people to heal after surgery, or treating diseases of ageing.

“It's very provocative,” says Mark Mattson, chief of the Laboratory of Neurosciences at the US National Institute on Aging in Bethesda, Maryland, who has not been involved in the parabiosis work. “It makes you think. Maybe I should bank some blood of my daughter's son, so if I start to have any cognitive problems, I'll have some help,” he says, only half-joking.

The power of two

Physiologist Paul Bert performed the earliest recorded parabiosis experiment in 1864, when he removed a strip of skin from the flanks of two albino rats, then stitched the animals together in hopes of creating a shared circulatory system1. Biology did the rest: natural wound-healing processes joined the animals' circulatory systems as capillaries regrew at the intersection. Bert found that fluid injected into a vein of one rat passed easily into the other, work that won him an award from the French Academy of Sciences in 1866.

Since Bert's initial experiments, the procedure has not changed much. It has been performed on hydra — small freshwater invertebrates related to jellyfish — frogs and insects, but it works best on rodents, which recover well from the surgery. Up to the mid-twentieth century, scientists used parabiotic pairs of mice or rats to study a variety of phenomena. For example, one team ruled out the idea that dental cavities are the result of sugar in the blood by using a pair of parabiosed rats, of which only one was fed a daily diet of glucose. The rats had similar blood glucose levels owing to their shared circulation, yet only the rat that actually ate the sugar developed cavities2.

Nik Spencer/Nature; Chart Data: A. Eggel & T. Wyss-Coray Swiss Med. Wkly 144, W13914 (2014)

3. The linked rats included a 1.5-month-old paired with a 16-month-old — the equivalent of pairing a 5-year-old human with a 47-year-old. It was not a pretty experiment. “If two rats are not adjusted to each other, one will chew the head of the other until it is destroyed,” the authors wrote in one description of their work4. And of the 69 pairs, 11 died from a mysterious condition termed parabiotic disease, which occurs approximately one to two weeks after partners are joined, and may be a form of tissue rejection.

Today, parabiosis is performed carefully to reduce animal discomfort and mortality. “We observe the mice at length and have long discussions with our animal-care committee,” says Thomas Rando, a Stanford neurologist who has used the procedure. “We don't take this lightly.” Mice of the same sex and size are socialized with each other for two weeks before attachment, and the surgery itself is done in a sterile setting with anaesthesia, heating pads and antibiotics to prevent infection. Using inbred lab mice, genetically matched to one another, seems to reduce the risk of parabiotic disease. Joined mice eat, drink and behave normally — and they can be separated successfully.

In McCay's first parabiotic ageing experiment, after old and young rats were joined for 9–18 months, the older animals' bones became similar in weight and density to the bones of their younger counterparts5. More than 15 years later, in 1972, two researchers at the University of California studied the lifespans of old–young rat pairs. Older partners lived for four to five months longer than controls, suggesting for the first time that circulation of young blood might affect longevity6.