theworldismine13

God Emperor of SOHH

http://www.economist.com/news/speci...oblem-trouble-isolation-new-kind?fsrc=rss|spr

“STOCKBRIDGE VILLAGE HAS always been an island,” says Bill Weightman, a local politician. The large public housing estate, a mixture of towers and two-storey homes, was built in the 1960s to accommodate people cleared out of Toxteth and other inner-city slums. Residents were expected to commute to jobs in Liverpool, five miles to the west.

Things began well, but Stockbridge gradually slid. In the ward that contains much of the estate, 42% of working-age adults depend on benefits. Low aspiration begets low aspiration. The local secondary school, Christ the King, inhabited a spectacular modern building. But its pupils did so poorly in exams that it was closed earlier this year.

Stockbridge is also one of Britain’s most concentrated urban ethnic ghettos. Locals aver that people with the wrong skin colour are no longer beaten up if they wander into the estate, as they were until recently. Then again, few take the risk. Fully 96% of the population of Stockbridge is of the same race: Caucasian.

Ghettos are normally thought of as black or Asian: the Bangladeshi housing estates of Tower Hamlets or the intensely African neighbourhood of Peckham, both in London. But Stockbridge Village qualifies, too. It is whiter than Britain or Merseyside as a whole, as well as far more homogeneously working-class. And it has social problems to match any ethnic-minority ghetto. Many of its inhabitants are ill. It is plagued by loan sharks. And its children are failing spectacularly. White 16-year-olds in Knowsley, the borough of which Stockbridge forms part, attain worse GCSE results than do black 16-year-olds in any London borough.

Stockbridge also features the internal policing sometimes found in stable, homogeneous places. Graffiti are few and far between. Several notorious criminals have lived in the estate, but they do not foul their own neighbourhood. Muggings are rare; victims would recognise their attackers. Car thefts used to be more of a problem, but Tosh Fielding, who runs a boxing club, says that matters have improved. He and others would make a few phone calls: no questions, no accusations, but the cars ought to be returned. They duly reappeared.

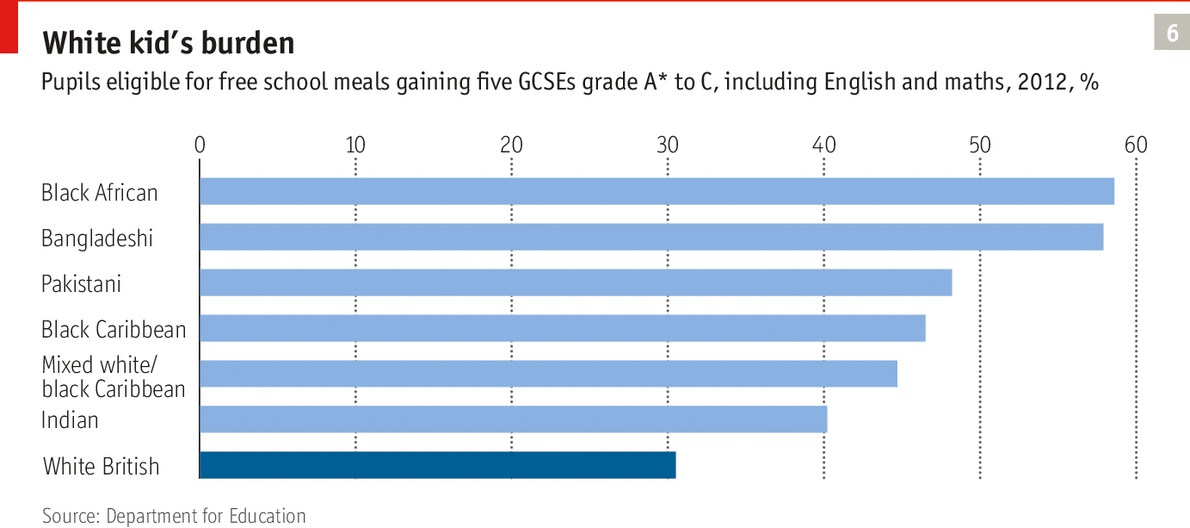

In short, Stockbridge Village is isolated. Its isolation is partly geographical—it is two miles from the nearest railway station, and three out of every five households have no car—but mostly cultural. Its residents are trapped in a cycle of low achievement and low earnings. So are many other working-class whites in other public housing estates in Britain. Nationally, poor whites fare worse at school than poor blacks or Asians (see chart 6).