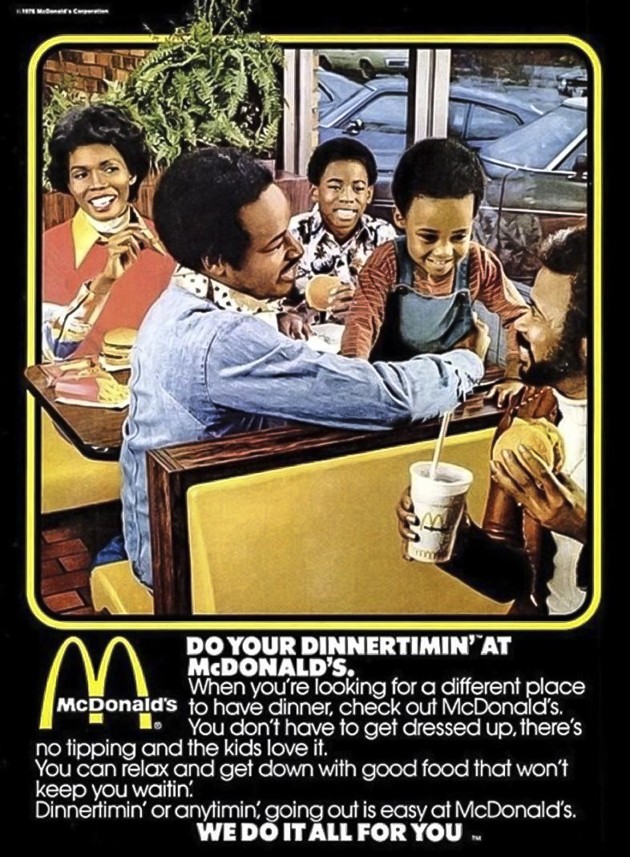

"there's no tipping"

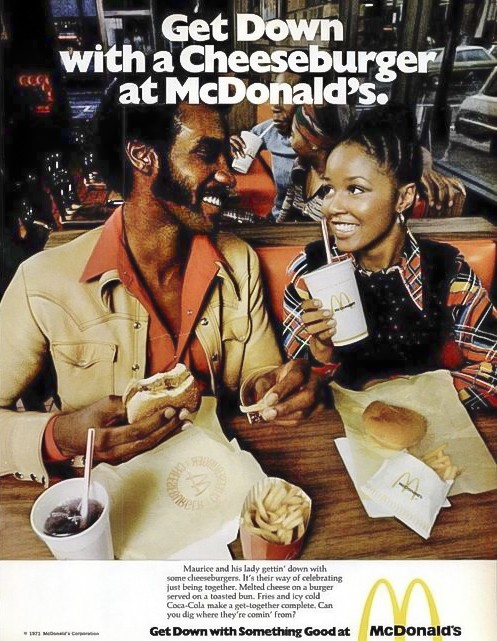

"Maurice and his lady gettin' down with some cheeseburgers" (you see how they left the "are" out of that sentence

)

)"can you dig where they're comin' from?"

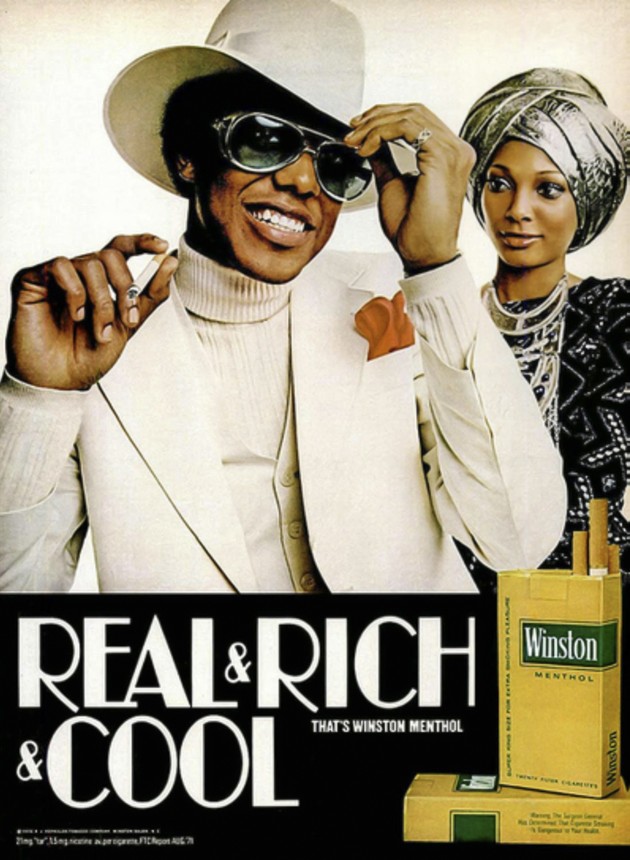

they got a pimp with the queen of Zamunda....

In the 1970s, something special began happening in American advertising. At the tail end of the civil-rights movement, the industry began to move away from its decades-long habit of portraying African Americans almost exclusively in positions of servitude or inferiority, as props in ads aimed at white audiences. By the 1970s, companies such as McDonald’s and Coca-Cola began increasing the racial diversity depicted in their campaigns. In 1974, Jello became one of the first big companies to hire an African American spokesperson—Bill Cosby. The goal was twofold for corporations: to keep up with the times, and to broaden their potential consumer base.

But the way many agencies went about this demonstrates how little they understood about their target demographic—and the results, like so many vintage ads, appear deeply misguided to modern audiences. To McDonald’s, for example, appealing to African American consumers specifically meant, in part, ads such as “Makin’ it” and “Dinnertimin,’” which made extensive use of “g-dropping.”

Ads featuring Caucasiansfrom around the same time, meanwhile, left out lines like “On the real, kids can really dig gettin’ down with McDonald’s” and the insidious “‘em.” Employing “g-dropping” to appeal to African American audiences has a long history, from Aunt Jemima’s much-maligned “mammy” ads (which used lines like “Every bite is happyfyin’ light”) in the early 20th century toPresident Barack Obama’s controversial speech to the Congressional Black Caucus in 2011.

Burger King played up this vernacular distinction in some of its “Have It Your Way” ads to a lesser extent, though one ad inexplicably interjected the line “Have mercy!!”

Charlton McIlwain, an associate professor at New York University who specializes in race and media, said in an email that he views these tone-deaf ads as “the outcome of [advertisers] trying to do the right thing, but not necessarily knowing what that meant.” White-dominated ad agencies lacked a general familiarity with blacks and black communities, leading them ”to design ads that were racially naive and necessarily relied on stereotypes for lack of any other information.”

Neil Drossman, an executive creative director and partner at his own ad agency, agreed, calling the McDonald’s ads “a really cynical and superficial effort to reach a black audience.” Drossman, who began working in New York ad agencies in the 70s, said he remembers his firm working on an ad featuring a black couple and being asked if it looked “too urban.” According to Drostman, most of the industry’s missteps resulted from an ignorance on behalf of mainstream ad companies (though there were and are specialized black agencies), but the general failure in tone was something that even the conventions of the era can’t really excuse. “What differentiated the good agencies of that period from the big, bad ones (the great majority) was a respect for the target and a desire to understand it,” Drossman said.

Advertisers knew empirically that African Americans were more likely to buy a product when they saw themselves reflected in ads—so targeted advertising made sense. But agencies also worried that products would become “branded black,” losing them their white consumers as a result. This turned out to be a misguided fear. Demographic targeting continued to flourish, and by the end of the decade, blacks made up around 12 percent of models in commercials, compared to 3 percent in the mid-1960s, McIlwain said.

If microtargeting is a legacy of 1970s advertising industry shifts, then so is the casual—or symbolic—racism that inevitably resulted. As the sociologist Anthony Cortese noted in his book Provocateur: Images of Women and Minorities in Advertising, “Stereotypes of blacks and ethnic minorities have not been eliminated but have changed in character, taking subtler and more symbolic or underhanded forms.” While advertisers took depictions of African American more seriously, other minorities were left out, largely because they had no significant spending power and weren’t worth pursuing.

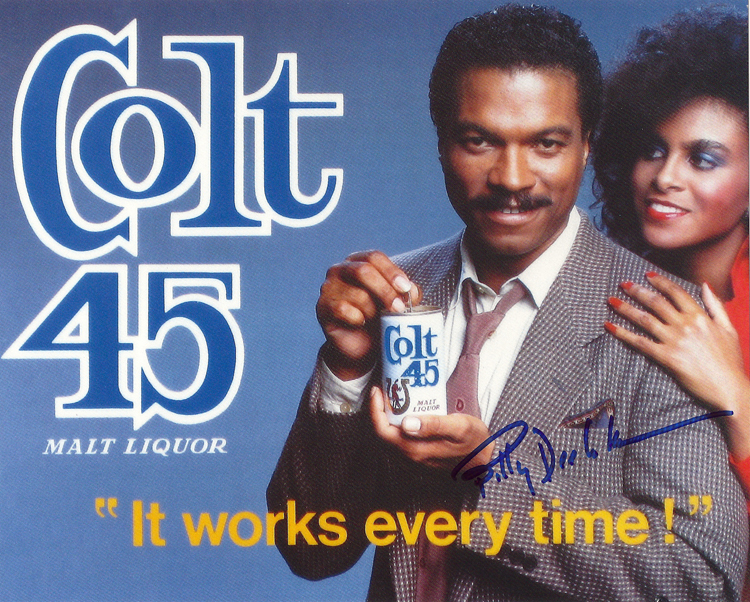

Not only did advertisers regurgitate stereotypes, but they also helped invent new ones. The 1970s also marks the beginning of advertisers targeting minorities in vice-related categories. Think alcohol and cigarettes, especially menthol, which companies such as Winston branded as “Real & Rich & Cool.” As middle-class white consumers began kicking their smoking habits in the 70s, agencies began advertising for cigarettes in predominantly black communities at 2.6 times the rate of white communities. Today, McDonald’s continues to run a website dedicated to promoting black culture called 365Black. As Imani Perry, a professor at Princeton University’s Center for African American studies toldDigiday in 2014:

McDonald’s direct marketing to African Americans has always troubled me, largely because so many African Americans live in urban areas surrounded by fast food restaurants and with limited access to fresh produce and unprocessed food. It seemed to add insult to injury to present this business as having any investment or interest in African American history and culture.

There is a difference, though, in the kind of reaction companies can expect today if an ad goes too far in an attempt to appeal to a certain demographic. “Businesses must weigh the benefit of potential profit to be gained from ethnic consumers against the risk of permanently alienating such large consumer markets,” Cortese said. “In the past, boycotts by ethnic consumers were successfully used for social change. Today's activists are much more hostile and bold. Demands that particular goods be taken off retail shelves have become more intense.”

Which is great news. The overall progress the advertising industry has made in depicting people of different backgrounds and lifestyles hasn’t made people any more complacent about the kinds of casually racist imagery so many promotions still resort to. Ashton Kutcher in brownface playing a character named Raj for PopChips? Backlash, and the ad got pulled. A Mountain Dew commercial featuring a goat suspected of beating up a woman telling a lineup of black men “You betta not snitch on a playa”? It was called “the most racist ad ever” and also got pulled. All of which goes to show that, even with decades of hindsight, agencies are still looking to the sensibilities of the public to keep them in check.

http://www.theatlantic.com/entertai...-greater-diversity-in-70s-advertising/394958/

@ making "dinnertimin" a verb

@ making "dinnertimin" a verb