@GzUp @wire28 @Atlrocafella @Blessed Is the Man @ezrathegreat @Jello Biafra @Chicken Pot Pie @humble forever @Darth Nubian @General Mills @88m3 @GinaThatAintNoDamnPuppy! @dtownreppin214

Was a Trump Server Communicating With Russia?

1.7k

6.2k

310

This spring, a group of computer scientists set out to determine whether hackers were interfering with the Trump campaign. They found something they weren’t expecting.

By Franklin Foer

Donald Trump gives a fist-pump to the ground crew as he arrives on his plane in St. Augustine, Florida, on Oct. 24.

Jonathan Ernst/Reuters

The greatest miracle of the internet is that it exists—the second greatest is that it persists. Every so often we’re reminded that bad actors wield great skill and have little conscience about the harm they inflict on the world’s digital nervous system. They invent viruses, botnets, and sundry species of malware. There’s good money to be made deflecting these incursions. But a small, tightly knit community of computer scientists who pursue such work—some at cybersecurity firms, some in academia, some with close ties to three-letter federal agencies—is also spurred by a sense of shared idealism and considers itself the benevolent posse that chases off the rogues and rogue states that try to purloin sensitive data and infect the internet with their bugs. “We’re the Union of Concerned Nerds,” in the wry formulation of the Indiana University computer scientist L. Jean Camp.

In late spring, this community of malware hunters placed itself in a high state of alarm. Word arrived that Russian hackers had infiltrated the servers of the Democratic National Committee, an attack persuasively detailed by the respected cybersecurity firm CrowdStrike. The computer scientists posited a logical hypothesis, which they set out to rigorously test: If the Russians were worming their way into the DNC, they might very well be attacking other entities central to the presidential campaign, including Donald Trump’s many servers. “We wanted to help defend both campaigns, because we wanted to preserve the integrity of the election,” says one of the academics, who works at a university that asked him not to speak with reporters because of the sensitive nature of his work.

Hunting for malware requires highly specialized knowledge of the intricacies of the domain name system—the protocol that allows us to type email addresses and website names to initiate communication. DNS enables our words to set in motion a chain of connections between servers, which in turn delivers the results we desire. Before a mail server can deliver a message to another mail server, it has to look up its IP address using the DNS. Computer scientists have built a set of massive DNS databases, which provide fragmentary histories of communications flows, in part to create an archive of malware: a kind of catalog of the tricks bad actors have tried to pull, which often involve masquerading as legitimate actors. These databases can give a useful, though far from comprehensive, snapshot of traffic across the internet. Some of the most trusted DNS specialists—an elite group of malware hunters, who work for private contractors—have access to nearly comprehensive logs of communication between servers. They work in close concert with internet service providers, the networks through which most of us connect to the internet, and the ones that are most vulnerable to massive attacks. To extend the traffic metaphor, these scientists have cameras posted on the internet’s stoplights and overpasses. They are entrusted with something close to a complete record of all the servers of the world connecting with one another.

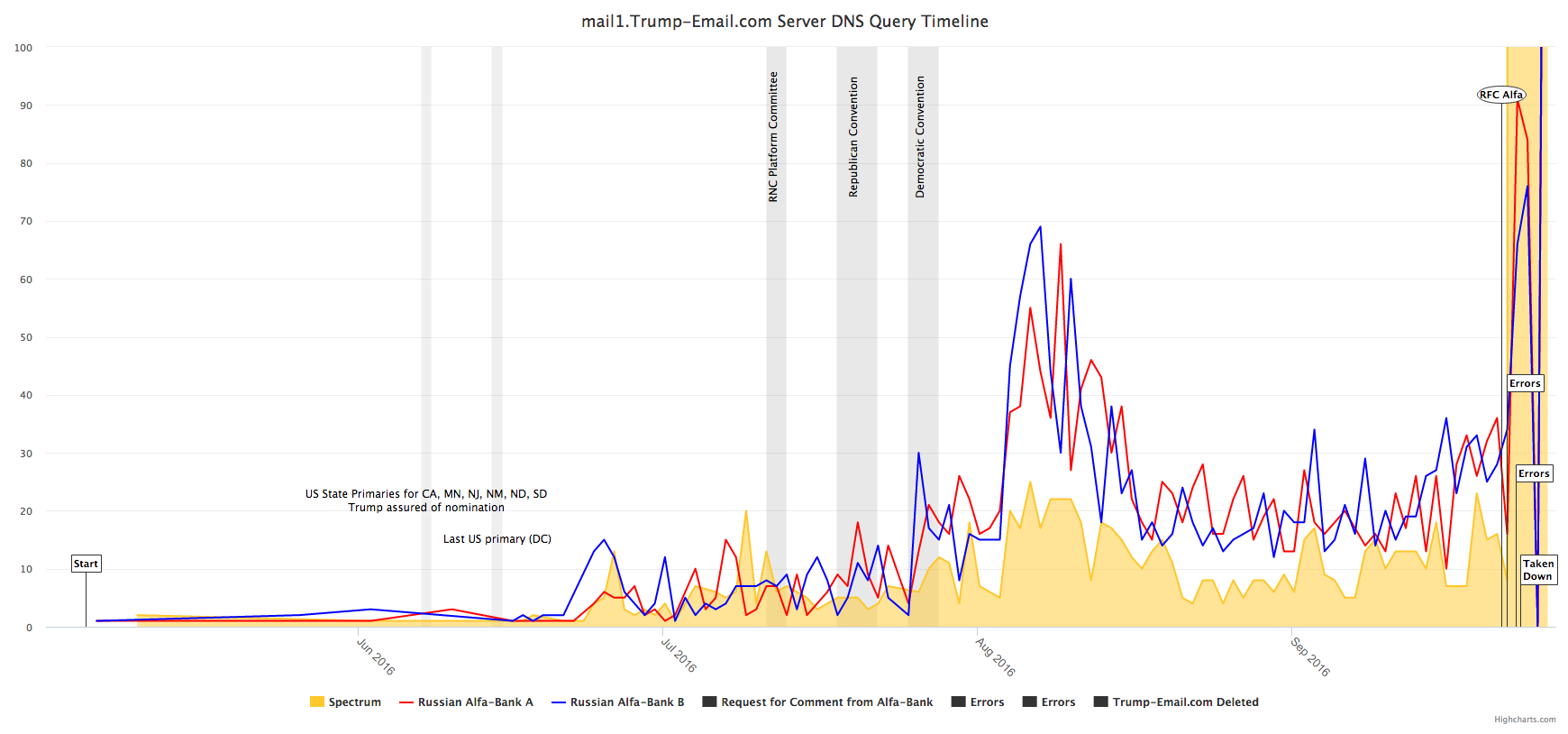

In late July, one of these scientists—who asked to be referred to as Tea Leaves, a pseudonym that would protect his relationship with the networks and banks that employ him to sift their data—found what looked like malware emanating from Russia. The destination domain had Trump in its name, which of course attracted Tea Leaves’ attention. But his discovery of the data was pure happenstance—a surprising needle in a large haystack of DNS lookups on his screen. “I have an outlier here that connects to Russia in a strange way,” he wrote in his notes. He couldn’t quite figure it out at first. But what he saw was a bank in Moscow that kept irregularly pinging a server registered to the Trump Organization on Fifth Avenue.

More data was needed, so he began carefully keeping logs of the Trump server’s DNS activity. As he collected the logs, he would circulate them in periodic batches to colleagues in the cybersecurity world. Six of them began scrutinizing them for clues.

Trump Tower.

Ullstein Bild/Getty Images

(I communicated extensively with Tea Leaves and two of his closest collaborators, who also spoke with me on the condition of anonymity, since they work for firms trusted by corporations and law enforcement to analyze sensitive data. They persuasively demonstrated some of their analytical methods to me—and showed me two white papers, which they had circulated so that colleagues could check their analysis. I also spoke with academics who vouched for Tea Leaves’ integrity and his unusual access to information. “This is someone I know well and is very well-known in the networking community,” said Camp. “When they say something about DNS, you believe them. This person has technical authority and access to data.”)

The researchers quickly dismissed their initial fear that the logs represented a malware attack. The communication wasn’t the work of bots. The irregular pattern of server lookups actually resembled the pattern of human conversation—conversations that began during office hours in New York and continued during office hours in Moscow. It dawned on the researchers that this wasn’t an attack, but a sustained relationship between a server registered to the Trump Organization and two servers registered to an entity called Alfa Bank.

The researchers had initially stumbled in their diagnosis because of the odd configuration of Trump’s server. “I’ve never seen a server set up like that,” says Christopher Davis, who runs the cybersecurity firm HYAS InfoSec Inc. and won a FBI Director Award for Excellence for his work tracking down the authors of one of the world’s nastiest botnet attacks. “It looked weird, and it didn’t pass the sniff test.” The server was first registered to Trump’s business in 2009 and was set up to run consumer marketing campaigns. It had a history of sending mass emails on behalf of Trump-branded properties and products. Researchers were ultimately convinced that the server indeed belonged to Trump. (Click here to see the server’s registration record.) But now this capacious server handled a strangely small load of traffic, such a small load that it would be hard for a company to justify the expense and trouble it would take to maintain it. “I get more mail in a day than the server handled,” Davis says.

Paul Vixie. In the world of DNS experts, there’s no higher authority. Vixie wrote central strands of the DNS code that makes the internet work. After studying the logs, he concluded, “The parties were communicating in a secretive fashion. The operative word is secretive. This is more akin to what criminal syndicates do if they are putting together a project.” Put differently, the logs suggested that Trump and Alfa had configured something like a digital hotline connecting the two entities, shutting out the rest of the world, and designed to obscure its own existence. Over the summer, the scientists observed the communications trail from a distance.

* * *

This is just pathetic even for you...One minute you say Trump is a retarded neo nazi..the next minute hes a russianJason bourne...then hes a megalomaniac out to rule the world...

This is just pathetic even for you...One minute you say Trump is a retarded neo nazi..the next minute hes a russianJason bourne...then hes a megalomaniac out to rule the world...

PS and thats retarded..Once you go past $1,000,000 dollar deals nobody checks credit anymore.....

PS and thats retarded..Once you go past $1,000,000 dollar deals nobody checks credit anymore..... thats why you cant understand such things with a broke nikka perspective

thats why you cant understand such things with a broke nikka perspective