As promised, here is another thread from my "Lets talk African history" series. And again as a theme of the series this is a non-Ancient Egyptian African civilization. Yet another African civilization by Bantu people, who I consider a very underrated group, the Swahili civilization/city states. Many of us, especially us blacks in America know about the language, but not really the interesting civilization. To me the Swahili coast beats Ancient Egypt in some ways in terms of complexity. Their architecture alone is one of the best in Africa. Also they(and horner kingdoms like those from Somalis and Ethiopians) refute some of the biggest myths about Africans and that Africans somehow were too stupid to sail and go into the seas. Well Swahili culture was big in sailing, especially living off the coast and having to trade. That's why I also find them interesting. And back to architecture, I also find them interesting that they mostly built in stone. Which is kinda unique as most African cultures including even the Ancient Egyptians built in either mudbrick or wood. They are also unique in that their language and culture is a mixture between a lot outside influences like Arab, Persian and I even heard Chinese!!!

Though the downside of the Swahili civilizations is that a good number of them would be what we call "c00ns", especially those from Zanzibar who specialized in selling slaves from the interior to Arabs and were the main ones. But other than that Kilwa and Mombasa said to very beautiful by outsiders. And if I remember correctly the people of the Swahili coast were the Zanjs.

But before I continue with this thread, we have to go back in time. Since who occupied the Swahili coast has always been up in debates. Historians use to try to say it was either Arabs or Persian. Luckily that has been debunked...Especially by a Swahili archaeologist himself.

BBC News | AFRICA | Tanzanian dig unearths ancient secretA discovery which a Tanzanian archaeologist believes will change how East African history is regarded has been made on tiny Juani Island, off the Tanzanian coast.

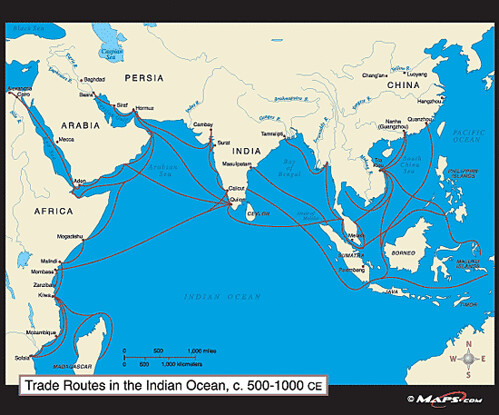

Felix Chami, professor of archaeology at the University of Dar es Salaam has uncovered a major site on Juani, near Mafia Island, which he believes will substantially increase the evidence that East Africa was part of a wider Indian Ocean community.

Previous to Dr Chami's other discoveries on the Tanzanian coast, scholars had never considered East Africa as part of the ancient world.

The professor had been alerted to the existence of the cave by two local men who informed Peter Byrne, owner of a small lodge on Mafia Island and supporter of efforts to discover the intriguing history of these small islands - which are now entirely dependent on fishing.

Cave spirits

We sailed on a dhow from Mafia Island to a beach on nearby Juani Island which Dr Chami believes may have been an ancient port since the Iron Age.

Unlike the other islands, Juani has fresh water and soil suitable for agriculture.

The two local men, whose curiosity had overcome beliefs that the caves are inhabited by spirits, led us more than a kilometre along jungle tracks.

The men hacked a path through the luxuriant growth with pangas which revealed a collapsed coral cave around 20 metres in diameter.

With the help of hanging vines we climbed down into the cave.

Major site

Scattered throughout the seven to 10-metre-high overhanging cave were shards of pottery, human bones and three skulls.

Dr Chami examined the skulls but said only carbon dating would establish their age.

He was most excited by the large habitable area of soft loose soil, at least 50 square metres.

"There could be three metres of layers here to establish a cultural chronology," he says.

"This is a marvel. I believe this was a major Iron Age site. I can assure you this will change the archaeology of East Africa."

Felix Chami will return to the site with his team after the rainy season to start a full excavation.

In the past five years Dr Chami has overturned the belief that Swahili civilisation was simply the result of Indian Ocean trade networks.

Trade secrets

"It was thought that Swahili settlements were founded by foreigners, particularly by Islamic traders," he says. "But these discoveries show the people here were interacting with other civilisations - and long before the Islamic era."

Dr Chami believes the coastal communities may have been trading animal goods, such as ivory as well as iron.

Dr. Chami utilised the writings of Greek geographer Ptolemy (c.87-150 AD) who described settlements in East Africa as "metropolis" and also referred to "cave dwellers".

Ptolemy even specified a latitude eight degrees south on a large river -the location of the Rufiji river.

It was there on the hills above the river that Dr Chami found the remains of settlements with ancient trading goods and evidence of agriculture.

Directly opposite the Rufiji delta are Mafia & Juani Islands.

Dr Chami's excavations uncovered cultural artefacts which have been carbon dated to 600 BC.

They included Greco-Roman pottery, Syrian glass vessels, Sassanian pottery from Persia and glass beads.

But Felix Chami believes the new site on Juani Island may well be the most significant yet.

^^^Now what you look at that... The so called "inferior Bantus" not only occupied the Swahili coast first, but they were trading with major civilizations such as the Greeks/Romans and Persians since antiquity. Meanwhile the Arabs were still in their deserts in Arabia and were mostly isolated.

But more importantly there goes the myth that Africans from the interior were largely isolated from the world.

Anyways adding on to the Swahili origins.

Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western CulturesThe Origin of The Swahili Towns

Scholars had, up to the end of the twentieth century, debated the origin of the Swahili people and their stone town culture. Such debates revolved on the question of who the Swahili people were (Allen 1974, 1983; Nurse and Spear 1985; Pouwels 1987; Horton 1987; and Chami 1994, 1998). The original popular conception was that the Swahili people and their culture originated from the Middle East. These were alleged to have arrived in waves of immigration. Individuals in these waves founded settlements, which later grew into larger Swahili stone towns. Chittick (1974, 1975) used chronicles, particularly that of Kilwa, and archaeology to argue that the earliest immigrants could have arrived on the East African coast not earlier that the ninth century. This view suggested, therefore, that the Swahili people were originally Persians or Arabs who would later have mixed with Africans. Due to their alleged origin in the Muslim world the Swahili people were necessarily Muslims and people of towns.

Archaeologists such as Horton (1987), influenced by Allen (1983), suggested that the Swahili were people of Cushytic origin, from the northeast of Africa, who were originally pastoralists. The pastoralists, who are alleged to have ruled the Bantu speakers in a mythical land called Shunguaya, mixed with Bantu speakers, adopted Islam and spread to the rest of the coast and islands of East Africa. In this theory the Swahili people are seen as Africans who also mixed with the people of the Middle East in the process of adopting Islam and trade. This position was made more prominent in the 1990s (Horton 1990; Abungu 1994–1995; Sutton 1994–1995) in an attempt to quash the discovery that the Swahili people were Africans of Bantu origin, people of the general region of Eastern and Southern Africa who were agriculturalists and fishermen.

That the Swahili people did speak a Bantu language was a point recognised by linguists from the 1980s (Nurse and Spear 1985). Archaeologists had also established settlements of Early Iron Working people near the coast; scholars recognised that they were early Bantu speakers (Soper 1971; Phillipson 1977). Historians also recognised that the people reported by the Romans in the first centuries AD to have inhabited East Africa, then known as Azania, were agriculturalists and probably Bantu speaking (Casson 1989). In the early 1990s this author suggested that the cultural tradition found in the earliest Swahili settlements was culturally related to that of the Early Iron Working tradition (Chami 1994). In some cases settlements of the Early Iron Working people and those of the so‐called early Swahili, termed by this author as Triangular Incised Ware tradition, were found in the same location. In some cases the later was found superimposed over the former in the offshore islands and on the coastal littoral of the central coast of Tanzania (Chami 1998, 1999a).

The evidence of cultural continuity from the time of Christ, through the mid‐first millennium AD, to the time of the foundation of the Swahili towns in the early centuries of the second millennium AD, has now been recognised by many scholars (Kusimba 1999; Sinclair and Hakansson 2000; Spear 2000). Those who disagreed with the the first set of evidence for this continuity have now revised their ideas (Horton 1996; Horton and Middleton 2000; Sutton 1998). Archaeological findings now prove that the Swahili coast had been settled by an agricultural and trading population from the time of Pharaonic Egypt, 3000 BCE, through the Greaco‐Roman period (Chami 2006). Whereas the former was of Neolithic tradition, the latter was an Early Iron Working culture. Throughout these periods the Indian Ocean, just like it was during the time of Islam, had brisk trade with communities of Asia, the Middle East and the Red Sea/Mediterranean worlds. Ceramics and beads as evidence of trade of all these pre‐Islamic trading periods have now been recovered from the islands of Zanzibar, Mafia, Kilwa and Rufiji River (for conspectus see Chami 1999b, 2004, 2006).

The most recent thinking that the early Swahili people, or Zanj of the Arab documents, were Indonesians/Austronesians (dikk‐Read 2005) is an attempt to disregard the archaeological, linguistic and historical data already established. For this recent thinking to be regarded as scientific at least a discussion of the previous thinking on the subject matter and its flaws should have be debated.

Some Cultural Aspects of the Swahili Towns

General Culture

The culture of the Swahili towns, as already suggested, is African with an infusion of Islamic traits. It is these infused Islamic traits such as religion, law, language, writing and costume which have made many students of the Swahili culture identify the people as Arabs. The people who had adopted this culture themselves wanted to be identified as Arabs or Persians. However, Ibn Baṭṭūṭa identified the people as ‘Sawahil’ and the earliest European visitors to the Swahili world, the Portuguese, identified the people as ‘Moors’ or ‘Suaili’ as opposed to Arabs.

De Barros, as Ibn Baṭṭūṭa did, also identified the Sultans of Kilwa as black people (Chittick 1975: 39). Barbosa, writing in about 1518, wrote, “Of the Moors there are some fair and some black, they are finely clad in many rich garments of gold and silk and cotton.” To show that the Swahilis were different from Arabs, the Queen of Kilwa in the mid‐eighteenth century wrote a letter calling home her people who had run away from the Arab/Omani domination of Kilwa to Mozambique. This was written in Kiswahili and not in Arabic; a Swahili letter suggesting that it was only the Europeans/Christians who were in conflict with the Arabs, but not the African/Swahili people (Omar and Frankl 1994).

Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg New York 2008

10.1007/978-1-4020-4425-0_8504

Helaine Selin

Cities and Towns in East Africa

Felix Chami