↓R↑LYB

I trained Sheng Long and Shonuff

I came across this PDF today while searching for getting my concealed carry license and figured I'd share it. The PDF has pictures/footnotes but long story short, cacery at it's finest:

http://www.georgiacarry.org/cms/wp-content/uploads/2007/11/racist-roots-of-ga-gun-laws.pdf

Georgia's Gun Laws – Racism, Oppression and White Supremacy

Georgia's gun laws were designed to disarm slaves, freedmen, and black Georgians. Whenever blacks used arms to fight against racism and discrimination, the General Assembly responded with laws criminalizing their actions. Georgia's gun laws were not a crime prevention measure; they were Georgia's way to perpetuate racism, oppression and white supremacy. These racist laws still apply in Georgia.

The Early Days – The First Gun Bans

From the founding days of Georgia, whites had a great fear of armed blacks rebelling against white power and privilege. In 1739, eighty slaves from Stono, South Carolina rebelled and killed twenty-five whites before they were defeated in a pitched battle by a better armed white militia. In August 1831, Nat Turner and seventy slaves and freedmen traveled from house to house through Southampton County, Virginia axing and beating to death all of the whites that they could find, including women and children. 57 white men, women and children were murdered during Turner’s two day killing spree.

The General Assembly responded to Nat Turner’s Slave Rebellion by enacting harsh laws limiting the rights of free blacks in Georgia and prohibiting the entry of free blacks from other states. Prior to this time, slaves and free blacks were allowed to have firearms during the weekdays when they had the permission of their owner or guardian. Slave children were often provided a gun and were tasked to shoot birds and other vermin on the plantation. Those practices ended when the General Assembly passed Georgia’s first gun ban. The 1833 law provided that “it shall not be lawful for any free person of colour in this state, to own, use, or carry fire arms of any description whatever.” The penalty was thirty-nine lashes and the firearm was to be sold and the proceeds given to the Justice of the Peace, akin to today’s Magistrate. In 1846, the Georgia Supreme Court held in Nunn v State that there was a constitutional right to carry a pistol openly in Georgia. Then two years later, the Georgia Supreme Court clarified in Cooper and Worsham v. Savannah that this right did not extend to free blacks. The court proclaimed that "Free persons of color have never been recognized here as citizens; they are not entitled to bear arms, vote for members of the legislature, or to hold any civil office." This ruling would form the basis for the expulsion of black legislators in 1868.

Camilla Massacre – Birthplace of the Public Gathering Prohibition

On September 19, 1868, several hundred blacks and Republicans, nearly all armed with muskets and shotguns, marched 25 miles from Albany to Camilla Georgia to protest the General Assembly’s expulsion of 32 newly elected black legislators. The elected black legislators were expelled on the grounds that the right to vote granted in the state constitution did not include the right to hold civil office. As the marchers arrived at Camilla’s courthouse, they were ambushed by a posse of white townsmen organized by Mitchell County Sheriff, Mumford Poore. The Sheriff's posse continued its assault on the marchers as they fled into the surrounding woods, killing and wounding them as they tried to escape. One of the fleeing blacks, Daniel Howard, was struck in the head with the butt of a gun while fleeing. He was forced to return to Camilla where he overheard the whites lamenting that if only the freedmen had come without arms, the whites would have surrounded the blacks and killed them all. Over a dozen blacks were killed and more than 30 were wounded in the massacre.

At the time of the Camilla Massacre, voting age black men outnumbered white men in 65 of Georgia’s 137 counties. Blacks represented 44% of the population of Georgia. The vision of armed blacks marching into Camilla sent fear into the outnumbered white elite who remembered Stono and Nat Turner. With the ratification of the 14th Amendment by Georgia in 1868, the legal construct that blacks were not entitled to the rights of citizenship was destroyed. In response, the General Assembly enacted, in October, 1870, a seemingly race-neutral law that they had intended to apply only to blacks. The law said, “no person in said State of Georgia be permitted or allowed to carry about his or her person any dirk, bowieknife, pistol or revolver, or any kind of deadly weapon, to any court of justice, or any election ground or precinct, or any place of public worship, or any other public gathering in this State, except militia muster-grounds.” The penalty was either “a fine of not less than twenty nor more than fifty dollars for each and every such offense, or imprisonment in the common jail of the county, not less than ten nor more than twenty days, or both, at the discretion of the court.”

As written, this public gathering law would have prevented the black marchers from carrying arms during their march to Camilla but not the townsmen waiting for them. The selective application of the law started immediately as the law was ignored by white supremacists that had armed themselves and gathered at the polls to prevent blacks and Republicans from voting on Election Day in November 1870.

The law and subsequent court decisions worked well enough that the General Assembly did not seek more laws aimed at disarming blacks until the twentieth century, when the circumstance of armed blacks defending their lives, neighborhoods and property during the Atlanta Race Riot forced the white elite to act once again.

Atlanta Race Riot – “Disarm The Negroes.”

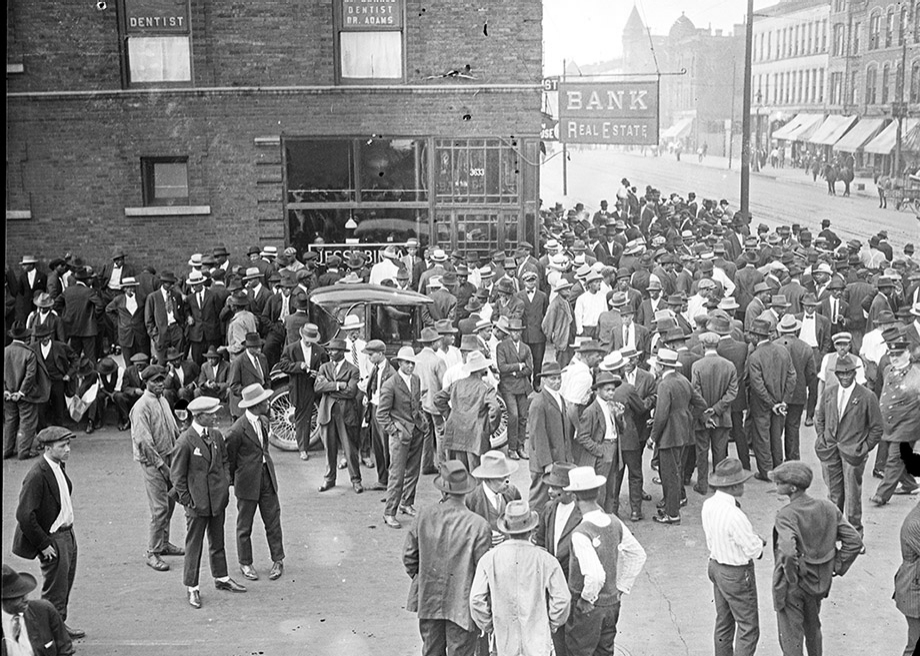

On Saturday, September 22, 1906, Atlanta exploded in racial violence that would last 4 days. During the months prior, the Atlanta Journal, Atlanta Constitution, and other newspapers published a continuous stream of sensational articles about a "Negro Crime Wave" involving black men sexually assaulting southern white women. The newspapers exaggerated facts and printed fabrications to inflame tensions in the city and increase their sales. On Saturday night, 5,000 white men and boys gathered at Five Points in downtown Atlanta. The newspapers enflamed the crowd's anger with their "extra editions" that were sold to the crowd with headlines of "Bold Negro Kisses White Girl's Hand", "Negro Attempts to Assault Mrs. Mary Cafin Near Sugar Creek Bridge", "Two Assaults", and "Third Assault". The "extra editions" and the newsboys who sold them challenged the white men to defend the honor of white women. After 9PM, the mob frenzy couldn't be contained and the mob surged in bloodlust in all directions away from Five Points.

The mob attacked and murdered with clubs, bottles, knives, bricks, and fists any blacks unfortunate enough to be seen by the mob. As the night went on, the whites escalated their attacks with guns and mutilated the bodies of their black victims. As fewer blacks were found on the streets, the mobs moved into the black neighborhoods to attack blacks in their homes. The next morning, the newspapers blamed the blacks for the violence. The headline in the Atlanta Constitution was “Atlanta Is Swept By Raging Mob Due To Assaults On White Women; Negroes Reported To Be Dead”. The headline from another newspaper was “Race Riots On The Streets Last Night The Inevitable Result Of A Carnival Of Crime Against Our White Women."

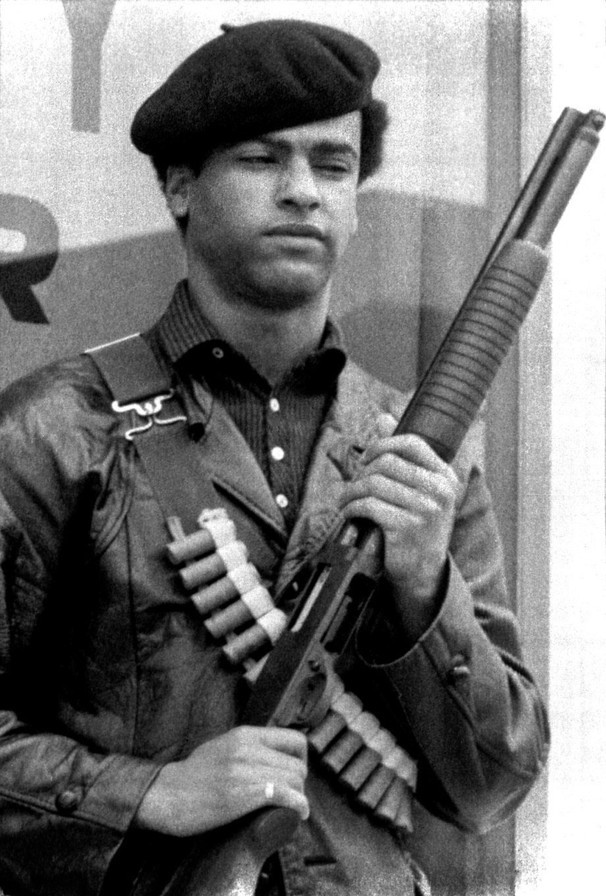

During the calm of daylight hours of Sunday, the black community armed themselves with smuggled guns hidden in rags, caskets, and lumber wagons. Although there was no law against blacks purchasing arms, the pawnshops and hardware stores refused to sell to them. Blacks who could pass for white bought weapons for themselves and their neighbors. Blacks bravely began to patrol their neighborhoods with weapons ready to stop attackers. One such neighborhood was Brownsville, a middle class black neighborhood south of Five Points and home to Clark University and Gammon Theological Institute. Many blacks from smaller communities sought refuge in the college buildings. In response to rumors of an impending attack by whites, armed blacks began to patrol the streets and gathered together for the purpose of defending their homes and families. On the night of Monday Sept 24th, seven Fulton County policemen and three armed white citizens arrived in Brownsville. Upon seeing a group of 25 armed black men congregated on the street, the Policemen divided up into squads and attacked the blacks from different directions.

By the end of the night, one police officer was killed and several whites were wounded. Six blacks were arrested for carrying concealed weapons. Two of the arrested blacks, still in their shackles, were killed hours later by a white mob. An unknown number of causalities were inflicted on the blacks that night.

In response to Monday night’s skirmish, the state militia, Fulton County Police, and the Governor’s Horse Guard were dispatched to Brownsville with orders to confiscate the black’s weapons. At dawn on Tuesday, the soldiers commenced a house to house sweep, ransacking the homes as they proceeded. The residents were evicted at the point of a bayonet from their homes and forced to assemble in the street. They were thoroughly searched for weapons under the watchful gaze of soldiers manning a Gatling gun with ten thousand rounds of ammunition. During the house to house search, Fulton County police officers accompanied by “deputized” white citizens found a black man severely wounded from the prior night’s battle. The police officers put their pistols to the man's chest and murdered him in front of his family. 257 black men were detained during the searches. 75 are arrested for possession of firearms and other weapons and transported to the county jail.

Later on Tuesday, the newspapers continued to blame the blacks for the rioting. The Atlanta Constitution front page headline read “Riot’s End All Depends On Negroes”. Another paper lamented, “The deepest spot in this crisis is in existence and liberty at large of Negroes heavily armed and full of malice and vengeance." The Atlanta Journal advocated the forcible disarming of all blacks in an editorial titled “Disarm the Negroes.” The Journal would get their wish in 1910, four years later.

http://www.georgiacarry.org/cms/wp-content/uploads/2007/11/racist-roots-of-ga-gun-laws.pdf

Georgia's Gun Laws – Racism, Oppression and White Supremacy

Georgia's gun laws were designed to disarm slaves, freedmen, and black Georgians. Whenever blacks used arms to fight against racism and discrimination, the General Assembly responded with laws criminalizing their actions. Georgia's gun laws were not a crime prevention measure; they were Georgia's way to perpetuate racism, oppression and white supremacy. These racist laws still apply in Georgia.

The Early Days – The First Gun Bans

From the founding days of Georgia, whites had a great fear of armed blacks rebelling against white power and privilege. In 1739, eighty slaves from Stono, South Carolina rebelled and killed twenty-five whites before they were defeated in a pitched battle by a better armed white militia. In August 1831, Nat Turner and seventy slaves and freedmen traveled from house to house through Southampton County, Virginia axing and beating to death all of the whites that they could find, including women and children. 57 white men, women and children were murdered during Turner’s two day killing spree.

The General Assembly responded to Nat Turner’s Slave Rebellion by enacting harsh laws limiting the rights of free blacks in Georgia and prohibiting the entry of free blacks from other states. Prior to this time, slaves and free blacks were allowed to have firearms during the weekdays when they had the permission of their owner or guardian. Slave children were often provided a gun and were tasked to shoot birds and other vermin on the plantation. Those practices ended when the General Assembly passed Georgia’s first gun ban. The 1833 law provided that “it shall not be lawful for any free person of colour in this state, to own, use, or carry fire arms of any description whatever.” The penalty was thirty-nine lashes and the firearm was to be sold and the proceeds given to the Justice of the Peace, akin to today’s Magistrate. In 1846, the Georgia Supreme Court held in Nunn v State that there was a constitutional right to carry a pistol openly in Georgia. Then two years later, the Georgia Supreme Court clarified in Cooper and Worsham v. Savannah that this right did not extend to free blacks. The court proclaimed that "Free persons of color have never been recognized here as citizens; they are not entitled to bear arms, vote for members of the legislature, or to hold any civil office." This ruling would form the basis for the expulsion of black legislators in 1868.

Camilla Massacre – Birthplace of the Public Gathering Prohibition

On September 19, 1868, several hundred blacks and Republicans, nearly all armed with muskets and shotguns, marched 25 miles from Albany to Camilla Georgia to protest the General Assembly’s expulsion of 32 newly elected black legislators. The elected black legislators were expelled on the grounds that the right to vote granted in the state constitution did not include the right to hold civil office. As the marchers arrived at Camilla’s courthouse, they were ambushed by a posse of white townsmen organized by Mitchell County Sheriff, Mumford Poore. The Sheriff's posse continued its assault on the marchers as they fled into the surrounding woods, killing and wounding them as they tried to escape. One of the fleeing blacks, Daniel Howard, was struck in the head with the butt of a gun while fleeing. He was forced to return to Camilla where he overheard the whites lamenting that if only the freedmen had come without arms, the whites would have surrounded the blacks and killed them all. Over a dozen blacks were killed and more than 30 were wounded in the massacre.

At the time of the Camilla Massacre, voting age black men outnumbered white men in 65 of Georgia’s 137 counties. Blacks represented 44% of the population of Georgia. The vision of armed blacks marching into Camilla sent fear into the outnumbered white elite who remembered Stono and Nat Turner. With the ratification of the 14th Amendment by Georgia in 1868, the legal construct that blacks were not entitled to the rights of citizenship was destroyed. In response, the General Assembly enacted, in October, 1870, a seemingly race-neutral law that they had intended to apply only to blacks. The law said, “no person in said State of Georgia be permitted or allowed to carry about his or her person any dirk, bowieknife, pistol or revolver, or any kind of deadly weapon, to any court of justice, or any election ground or precinct, or any place of public worship, or any other public gathering in this State, except militia muster-grounds.” The penalty was either “a fine of not less than twenty nor more than fifty dollars for each and every such offense, or imprisonment in the common jail of the county, not less than ten nor more than twenty days, or both, at the discretion of the court.”

As written, this public gathering law would have prevented the black marchers from carrying arms during their march to Camilla but not the townsmen waiting for them. The selective application of the law started immediately as the law was ignored by white supremacists that had armed themselves and gathered at the polls to prevent blacks and Republicans from voting on Election Day in November 1870.

The law and subsequent court decisions worked well enough that the General Assembly did not seek more laws aimed at disarming blacks until the twentieth century, when the circumstance of armed blacks defending their lives, neighborhoods and property during the Atlanta Race Riot forced the white elite to act once again.

Atlanta Race Riot – “Disarm The Negroes.”

On Saturday, September 22, 1906, Atlanta exploded in racial violence that would last 4 days. During the months prior, the Atlanta Journal, Atlanta Constitution, and other newspapers published a continuous stream of sensational articles about a "Negro Crime Wave" involving black men sexually assaulting southern white women. The newspapers exaggerated facts and printed fabrications to inflame tensions in the city and increase their sales. On Saturday night, 5,000 white men and boys gathered at Five Points in downtown Atlanta. The newspapers enflamed the crowd's anger with their "extra editions" that were sold to the crowd with headlines of "Bold Negro Kisses White Girl's Hand", "Negro Attempts to Assault Mrs. Mary Cafin Near Sugar Creek Bridge", "Two Assaults", and "Third Assault". The "extra editions" and the newsboys who sold them challenged the white men to defend the honor of white women. After 9PM, the mob frenzy couldn't be contained and the mob surged in bloodlust in all directions away from Five Points.

The mob attacked and murdered with clubs, bottles, knives, bricks, and fists any blacks unfortunate enough to be seen by the mob. As the night went on, the whites escalated their attacks with guns and mutilated the bodies of their black victims. As fewer blacks were found on the streets, the mobs moved into the black neighborhoods to attack blacks in their homes. The next morning, the newspapers blamed the blacks for the violence. The headline in the Atlanta Constitution was “Atlanta Is Swept By Raging Mob Due To Assaults On White Women; Negroes Reported To Be Dead”. The headline from another newspaper was “Race Riots On The Streets Last Night The Inevitable Result Of A Carnival Of Crime Against Our White Women."

During the calm of daylight hours of Sunday, the black community armed themselves with smuggled guns hidden in rags, caskets, and lumber wagons. Although there was no law against blacks purchasing arms, the pawnshops and hardware stores refused to sell to them. Blacks who could pass for white bought weapons for themselves and their neighbors. Blacks bravely began to patrol their neighborhoods with weapons ready to stop attackers. One such neighborhood was Brownsville, a middle class black neighborhood south of Five Points and home to Clark University and Gammon Theological Institute. Many blacks from smaller communities sought refuge in the college buildings. In response to rumors of an impending attack by whites, armed blacks began to patrol the streets and gathered together for the purpose of defending their homes and families. On the night of Monday Sept 24th, seven Fulton County policemen and three armed white citizens arrived in Brownsville. Upon seeing a group of 25 armed black men congregated on the street, the Policemen divided up into squads and attacked the blacks from different directions.

By the end of the night, one police officer was killed and several whites were wounded. Six blacks were arrested for carrying concealed weapons. Two of the arrested blacks, still in their shackles, were killed hours later by a white mob. An unknown number of causalities were inflicted on the blacks that night.

In response to Monday night’s skirmish, the state militia, Fulton County Police, and the Governor’s Horse Guard were dispatched to Brownsville with orders to confiscate the black’s weapons. At dawn on Tuesday, the soldiers commenced a house to house sweep, ransacking the homes as they proceeded. The residents were evicted at the point of a bayonet from their homes and forced to assemble in the street. They were thoroughly searched for weapons under the watchful gaze of soldiers manning a Gatling gun with ten thousand rounds of ammunition. During the house to house search, Fulton County police officers accompanied by “deputized” white citizens found a black man severely wounded from the prior night’s battle. The police officers put their pistols to the man's chest and murdered him in front of his family. 257 black men were detained during the searches. 75 are arrested for possession of firearms and other weapons and transported to the county jail.

Later on Tuesday, the newspapers continued to blame the blacks for the rioting. The Atlanta Constitution front page headline read “Riot’s End All Depends On Negroes”. Another paper lamented, “The deepest spot in this crisis is in existence and liberty at large of Negroes heavily armed and full of malice and vengeance." The Atlanta Journal advocated the forcible disarming of all blacks in an editorial titled “Disarm the Negroes.” The Journal would get their wish in 1910, four years later.

Last edited:

I hate living in this country and still in school

I hate living in this country and still in school